New Delhi, India – For years, Pravin Tambe, a leg-spinner from a middle-class family in Mumbai, toiled away in company and club teams with the singular goal of playing first-class cricket.

He kept going, even as he aged and other players began to refer to him as “uncle”.

Then in 2013, at the age of 41, he was discovered and signed by former Indian captain Rahul Dravid to play for a professional franchise cricket team.

In the 2014 edition of the Indian Premier League (IPL), while playing for Rajasthan Royals, Tambe took a hat-trick against Kolkata Knight Riders and was named man of the match. He went to the dressing room and wept.

His story was dramatised in the 2022 Bollywood biopic Kaun Pravin Tambe? (Who is Pravin Tambe?), whose character was played by actor Shreyas Talpade.

When Talpade auditioned for the role, his career was not going well.

“I was told that some people weren’t sure whether I’d be able to pull it off,” Talpade, now 47, told Al Jazeera.

He practised hard to convincingly play the leg-spinner from the ages of 20 to 41. His body ached, and one evening when he was feeling particularly low, Talpade and his wife watched Iqbal, his 2005 Bollywood film.

In Iqbal, Talpade played the fictional lead character, a deaf and mute village boy obsessed with playing cricket for India. Despite Iqbal’s disability, his father’s disapproval and no formal training, he persisted and, as happens in all good sports films, human spirit and grit triumph in the climactic sequence.

“[I watched it] just as a reminder – not only about the story of this guy, but also to myself – that I’ve done this before and I can do it again,” he said.

Talpade triumphed too. He got to play Tamble, and cricket transcended from being just a sport to become – as many Indians say – a “metaphor for life”.

People still come up to Talpade to tell him that when they are “feeling down,” they often watch Iqbal.

“The underdog factor is probably the crux. It’s very high on energy and motivation,” says Talpade.

The story of Indian cricket is the story of India, of Talpades and Iqbals, of men and women struggling with poverty, caste, class and gender discrimination, yet rising from gully cricket to play for the country – which is hosting the 2023 Cricket World Cup.

Bollywood, India’s “dream machine”, has always reflected the mood of the nation by drawing inspiration from real life – including from cricket, although it has had a rocky relationship with the sport.

“Cricket and cinema really are two religions in this country,” says Kabir Khan, one of Bollywood’s top directors whose last film, titled 83, was about India winning the World Cup for the first time in 1983.

“Having said that, we probably should have had more cricket films.”

The long cricket-Bollywood ‘jinx’

Bollywood’s love affair with cricket began on a sticky wicket in the late 1950s, when a black and white film, Love Marriage, was released.

That was a time when cricket was played professionally only in its longest form – Tests – over five days. Though the game and cricketers were very popular, the slow pace of Test cricket did not particularly lend itself to on-screen drama.

Love Marriage was about love, but it cast cricket as cupid, making the young heroine fall for her dashing tenant when he scores a century.

For several years after Love Marriage, there was no cricket on the silver screen. But in the 1970s, when India beat England in England, and the West Indies in the West Indies – where batsman Sunil Gavaskar, having scored 774 runs in his debut Test series, was celebrated with a calypso song – cricketers became stars and even began appearing in films.

Gavaskar sang, danced and screamed “I love you” in a Marathi language film, and Salim Durani, a dashing Afghan-born Indian all-rounder known for hitting boundaries on fans’ demand, was cast as the romantic lead in a rather dreary Bollywood film, titled Charitra (Character).

Although these films did not do well at the box office, Bollywood began warming up to the idea of releasing cricket-related films around big tournaments and wins to cash in on the cricket craze.

In the 1980s, after India won their first World Cup, two cricketers from the winning squad were cast in a Bollywood film: batsman Sandeep Patil played the romantic interest of two women in a film, titled Kabhie Ajnabi The (We Were Strangers Once), with wicketkeeper Syed Kirmani playing a baddie.

In the same decade, two terribly tacky films, whose fictional plot involved a rivalry between cricketers, were also released. One was a romantic melodrama, and the other, Awwal Number (Number One), was plain bizarre. Its climatic sequence involved two helicopters and a cricketer, miffed at being dropped, trying to blow up a pitch where an India vs Australia match was under way.

“The cricket [in these films] was lame,” Vasan Bala, a Bollywood writer-director, told Al Jazeera.

“Growing up, we just knew that cricket and Bollywood never work. It was a completely jinxed thing.”

One film changed that.

The film that broke the jinx

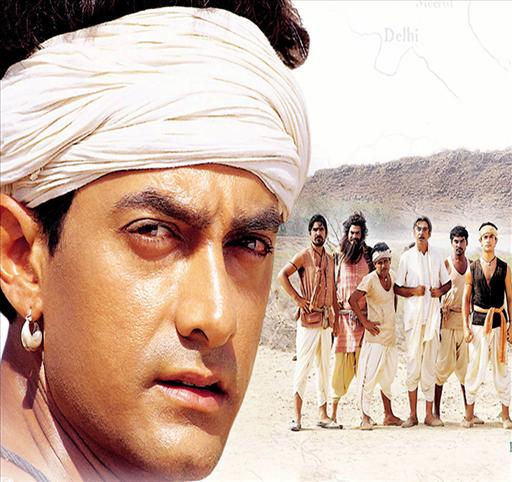

Lagaan: Once Upon A Time In India, directed by Ashutosh Gowarikar with Bollywood star Aamir Khan in the lead, was released in 2001.

It was a massive hit and was nominated in the Best Foreign Film category at the Academy Awards.

Lagaan did not win, but it broke the jinx at home. It also split India’s cricket-in-cinema story into two – the drought before Lagaan, and the deluge after.

Set in the 1890s during the British Raj, in an Indian village that is reeling under drought and heavy taxation, the story of Lagaan (Tax) was not just about cricket. It was about colonial injustice, caste discrimination and moral conviction.

The film’s fictional story took inspiration from the first “all-Indian” cricket team that toured England in 1911.

The three-hour-and-38-minute long film was about what a ragtag team of poor villagers — Hindus, including, a disabled Dalit man with a natural spin, a Sikh, and a Muslim — do after a British officer challenges them to a game of cricket: “Beat us and no tax will be levied for two years. But if you lose, the tax will be tripled.”

It was a classic David versus Goliath story with a bit of romance and nationalistic fervour thrown in.

“Lagaan was a very clever film … I remember watching it in a theatre where the entire cinema hall became a stadium,” said director and cricket buff Srijit Mukherji, whose biographical drama on Mithali Raj, a former captain of Indian women’s cricket team, released last year.

Lagaan came a year after cricket had suffered a devastating blow. In a shocking match-fixing scandal, then-India captain Mohammad Azharuddin was implicated along with others. The skipper, whose graceful batting and popped collar once stood for stylish integrity, had betrayed fans and tainted cricket.

“In Lagaan, the excitement was not about cricket. The excitement was about watching characters whose life depends on this game,” Bala says.

Lagaan’s motley crew of cricketers went some way to restoring faith in the game and spawned a whole new generation of cricket films, including several lookalikes in Bollywood and regional cinema that were set in small towns and gully tournaments.

Many were forgettable, but a few stood out.

As well as Iqbal, there was MS Dhoni: The Untold Story, released in 2016. Starring Sushant Singh Rajput as the eponymous lead, Dhoni, and directed by one of Bollywood’s leading directors, Neeraj Pandey, it is a biopic of India’s former captain, Mahinder Singh Dhoni.

It follows his journey from working as a ticket checker at a small railway station in a dusty town to leading India to win their second World Cup in 2011.

A less popular box office film, but no less influential, was 83.

A $34m cricket film

“A sports film is good only when it’s a good underdog story. And 1983 was a classic story of the underdog,” says director Kabir Khan. “I don’t think anything can ever be as exciting as 83 because post-83, we were never the underdogs.”

His 2021 feature film on India’s ascent to becoming world champions in England in 1983, at a time when British bookies were reportedly offering 50:1 against them, is a homage not just to an iconic tournament that is etched in India’s collective memory, ball-for-ball, wicket-to-wicket, but also to the moment at Lord’s when captain Kapil Dev raised the World Cup trophy and cricket shed its colonial legacy and became a part of India’s national identity.

“India is a country where everyone is a self-styled cricket pundit and they’re ready to give even Sachin Tendulkar tips on batting. My goal was to make a film where nobody could stand up and say, ‘This doesn’t look like the original,’” Khan said.

Khan’s team spent about two years researching the tournament, even managing to recreate a match – in Tunbridge Wells, Kent, where Kapil Dev scored 175 not-out against Zimbabwe – for which no footage existed.

Actors trained for months, and Ranveer Singh, one of Bollywood’s leading stars who played Kapil Dev, spent two weeks with the former captain; not just learning to walk, talk and play like him, but to also embody his peculiar style of reticent, gentle swagger.

In 83, cricket was stellar. But this cinematic coup came with a pricey tag. Made on a budget of $34m, 83 is one of the most expensive films ever made in India.

Critics praised the film, but four days after its release in December 2021, theatres in India began to shut down due to the third wave of COVID and the film was a box office flop.

But 83 set a new benchmark for cricket films and fired up many cinematic ambitions.

Bollywood has released five cricket films after 83, including Srijit Mukherji’s Shabaash Mithu, which traces Mithali Raj’s journey from a small town to leading India’s women’s cricket team to the final at the 2017 Women’s World Cup, which they lost to England.

“They lost the battle but they won the war against misogyny, against discrimination, against the sorry state of affairs of women’s cricket and inspired an entire generation of girls and women to pick up the sport,” Mukherji said.

There is authenticity in Shabaash Mithu’s cricketing action, but it flopped, as did all the other films.

The jinx seems to be back. Or, perhaps, genteel nostalgia and the underdog story no longer have resonance in a country that has changed.

‘Films reflect society’

In the sequel to every David versus Goliath story, David becomes Goliath.

India is now one of the fastest-growing economies in the world and a cricket powerhouse in terms of viewership and revenue.

Meanwhile, aggressive Hindu supremacism has soared since the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came to power in 2014.

“Cricket and cinema are the last bastions of secularism, but they are also a reflection of our society,” writer-director Varun Grover said.

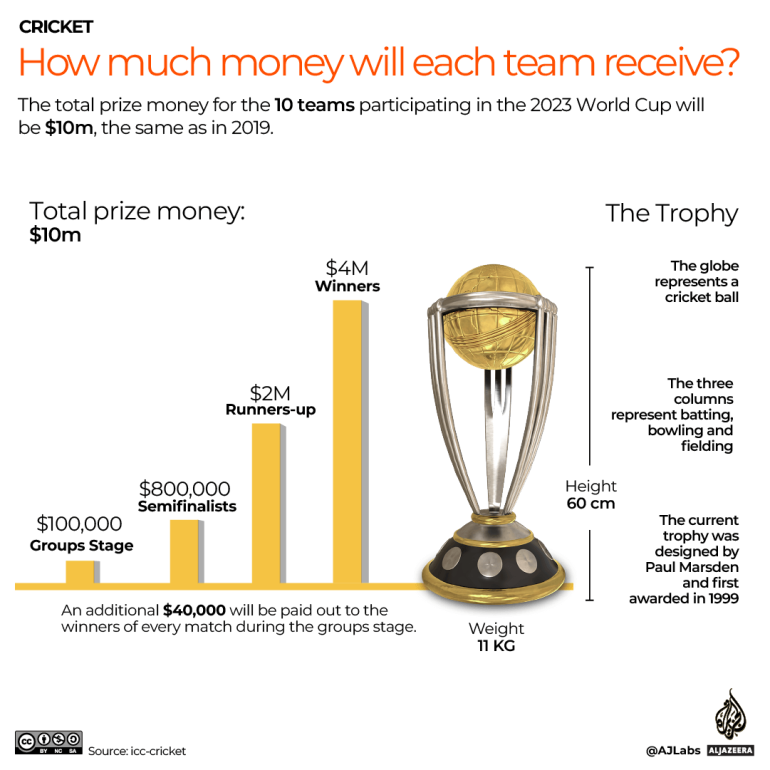

The India vs Pakistan Cricket World Cup match held in October was a blockbuster. Watched by 35 million viewers on Disney+Hotstar and more than 100,000 people in the stadium, for which tickets were reportedly sold for as high as 5,700,000 rupees ($69,170), the match was won by India.

But the crowds at Gujarat’s Narendra Modi Stadium, named after India’s prime minister, chanted “Jai Shri Ram” – a rallying cry of right-wing Hindus hailing a warrior God – as a taunt to Pakistani cricketers.

Another Bollywood film, titled Hukus Bukus, after a popular Kashmiri folk song, was released on November 3.

Set in Kashmir, it is a fictional story about a Hindu man desperately trying to build a temple dedicated to Hindu God Krishna in the contested Muslim-majority region, but he is up against Muslim politicians with vested interests. His son, a Tendulkar fan, plays a cricket match to get land for the temple.

“Films reflect society and its inflexions,” says Mukherji, “and cricket films are no different.”