Old City, occupied East Jerusalem – In the Christian Quarter, it doesn’t look a lot like Christmas this year.

There are almost no lights, no decorations and no Christmas trees.

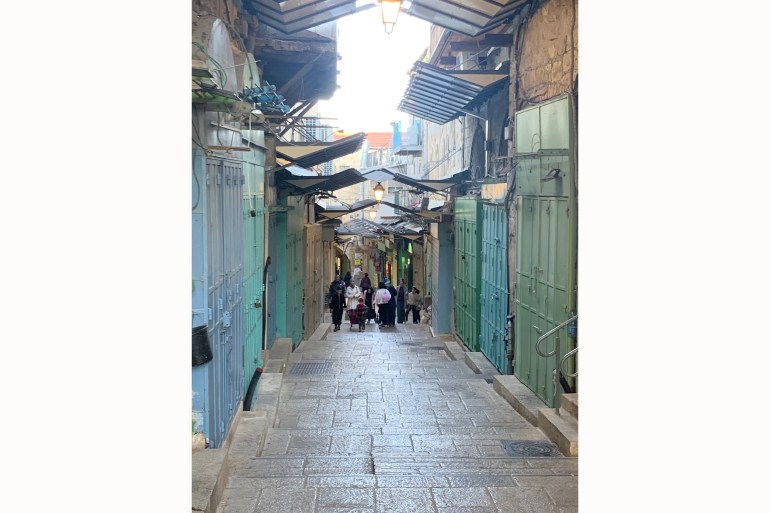

During a normal December, the aged limestone streets and alleys are brightly lit and bustling with pilgrims and locals alike, accompanied by Christmas carols from nearby shops.

On these silent nights and days, the streets are mostly empty.

“It doesn’t even feel like Christmas,” said Christo, a soft-spoken Palestinian shopkeeper from inside his Christian souvenir shop stocked with beautiful religious garments while angelic music plays in the background.

Even COVID-19’s economic devastation and the second Intifada’s blood-curdling violence did not affect Christmas celebrations in Jerusalem to such a degree. Many Palestinian Christians say this Christmas in Jerusalem is unprecedented for how devoid it is of Christmas joy.

“In the first and second Intifada, we had some difficult times,” said Bishop Emeritus of the Lutheran Church Munib Younan, 73, sitting next to a winter fire. “But it was different. Because we put up the [Christmas] trees. We wanted to bring joy in the times of difficulties. But now you see children [in Gaza] who have no home, who are hungry.

“To put [up] a tree is expressing a kind of joy,” said Bishop Younan. “And now is a time of sorrow. If you lose a member of your family, in our custom, you don’t put [up] a tree at that time. You concentrate that time on prayers.”

On November 10, the heads of the churches in Jerusalem released a joint declaration “to stand strong with those facing such afflictions by this year foregoing any unnecessarily festive activities”, calling instead to “advocate, pray and contribute generously” for the victims of the ongoing war.

Subsequently, all Christmas-related activities outside of prayer, whether it be the annual Christmas market near the New Gate or holiday parties and gatherings, have been cancelled. This Christmas, most families are making do with eating a simple meal and attending Mass.

“Every Christmas, we gather as a family with our parents, children, grandchildren – [this year], we don’t feel like doing this,” said Anton Asfar, secretary-general of Caritas Jerusalem, a Catholic relief, development and social services organisation, at his office. “We feel like we are doing something privileged, because others are suffering.”

In Gabi Hani’s home in the Old City, they put up a Christmas tree in private, “for the boys to at least have the meaning of Christmas for them”, he said. Hani’s three boys are aged 10, nine and five.

“The real psychological damage is not on me,” he said. “It is for the children that ask too many questions: ‘Is Hamas bad? Is Israel bad? Are Palestinians bad? The children are innocent. Why are they being killed? Which rocket is stronger?’

“I try to be diplomatic with my boys, not teaching hatred for the Israelis, for Jewish people. I try to say both sides should be better,” said Hani, who owns the Versavee Restaurant near Jaffa Gate – now closed. “It is difficult to teach my son these kinds of bitter realities at Christmas time.”

Glimmers of life in the streets of the Christian Quarter this Christmas appear for about half an hour in the afternoon when schools finish. All at once, the silence is broken by students in school uniforms scurrying along the limestone alleyways, the random Santa hat poking out among the buzzing children.

But within the Christian schools in Jerusalem – a bedrock of education for Palestinian children in Jerusalem for Christians and Muslims alike – there are few signs this year that it is Christmas.

At the College des Freres school at New Gate, Principal Brother Daoud Kassabry said there are no Christmas trees in classrooms or decorations in their office as there usually would be. The only sign of Christmas is a Nativity scene they put up in front of the church. “The young children, five, six years old – they are asking us where are our gifts for Christmas, because we had no gifts for them this year,” said Brother Kassabry.

A growing economic crisis

After enduring weeks of school closures at the start of the war, the Christian schools system in Jerusalem is facing economic pressures as parents struggle to pay for tuition. Unemployment has risen sharply since the start of the war with crippling movement restrictions and a near-total shutdown of tourism.

While schools have tried to accommodate families’ declining economic circumstances – dividing school fees into smaller payments or foregoing them altogether for those in need – the financial prospects for parents and, subsequently, schools are worsening.

“Without a change, the educational system will collapse sooner or later,” warned Asfar of Caritas.

With the tourists and pilgrims gone and local families losing income, most businesses in the Christian Quarter remain shuttered. Unable to make sustainable margins, Gabi Hani closed his Versavee Restaurant near Jaffa Gate during the first week of the war, leaving his 15 staff members out of work.

The shopkeepers, meanwhile, have completely lost out on their most lucrative tourism season leading up to Christmas.

“During the high season of November and October, you make a great amount of money that will support you through the whole year,” said Christo of his souvenir shop in the Christian Quarter.

But this season, “the streets are empty, so usually I don’t open at all”, said Christo. “I’m just trying to open because we’re trying to survive. But as you can see, there’s no work at all.

“It’s sad when you see Jerusalem like this,” he continued. “It’s like we are besieged.”

For some, the economic need has reached alarming levels in expensive Jerusalem.

“We are approached by people who end up with nothing to eat in the middle of the month,” said Asfar of Caritas, the relief organisation. “People are knocking on our doors just begging to pay their bills, buy bread, the most basic needs. They don’t want to beg for money. They want to work. They want to live in dignity.”

‘At a loss to comprehend attacks’

Many Palestinian Christians in Jerusalem are loath to receive anyone’s pity while they watch the death and destruction unfolding in Gaza. Among the 20,000 Palestinians killed, at least 24 Palestinian Christians have been killed in Gaza, where fewer than 1,000 Christians remain.

In October, Israeli shelling of St Porphyrius Greek Orthodox Church in Gaza, where hundreds of displaced Palestinians were sheltering, killed 18 Christian Palestinians and destroyed part of the 12th-century building.

On December 16, the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem said an Israeli sniper had shot and killed a Christian mother and daughter, Nahida Anton and Samar Anton, “in cold blood”, inside the compound of the Holy Family Parish in Gaza, where most Christian families have sought refuge since the war started.

The Latin Patriarchate, which is based at the Catholic Church in Jerusalem, said seven others were shot and wounded during the attack, which also destroyed water tanks and solar panels critical for the survival of families sheltered there.

The patriarchate’s statement added that a missile fired from an Israeli tank targeted the adjoining Convent of the Sisters of Mother Teresa in Gaza City, home to 54 severely disabled adults and children, and destroyed the building’s generator and fuel resources. Two more missiles targeting the convent had rendered it “uninhabitable”, the patriarchate said, displacing the disabled people sheltering there, some of whom are now without life-saving respirators.

The Israeli army has denied the claim.

Pope Francis has publicly condemned the killings and the Latin Patriarchate said it was “at a loss to comprehend how such an attack could be carried out, even more so as the whole Church prepares for Christmas”.

Father Firas Abedrabbo, 39, who serves in the Roman Catholic Parish of the Annunciation in Ein Arik, told Al Jazeera he had met Nahida and Samar many times while visiting Gaza with the Latin Patriarch in past years to spend Christmas there with local parishioners.

“When you know the person personally, the pain is doubled,” said Father Firas. “Don’t convince me that these two older ladies were dangerous for the national security of Israel when they were just passing in the courtyard of their church to go to the toilet.”

Back at the Caritas office, Asfar said two of the organisation’s staff members in Gaza have been killed since the start of the war. Viola Amash, a 26-year-old lab technician, was killed in St Porphyrius along with her husband, infant daughter, sister, brother-in-law and her sister’s children. In a separate rocket strike, another staff member was killed along with his entire family, sparing only his three-year-old daughter.

A picture of Viola now sits in a frame behind the front desk. Asfar, a usually jovial man with a signature chuckle, has held several support sessions for staff members “to help get them out of this trauma, because they keep crying,” he explained gravely.

With the entire surviving Christian community in Gaza displaced – and many of their homes destroyed or damaged – the belief is growing among church officials like Bishop Younan that, following this war, all the Christians left in Gaza will emigrate from the Holy Land.

“I’ve received many, many calls from [Christians in] Gaza who are waiting for visas,” said Brother Kassabry of College des Freres. “They want visas to Canada, Europe, anywhere.”

Meanwhile, church leaders and community members speak with growing alarm regarding the Christian presence in Jerusalem, which now numbers fewer than 20,000.

“Many families say that they don’t feel the future is safe for their children,” said Brother Kassabry.

Already coping with separate identification systems and movement restrictions before the war – and now watching loved ones in Gaza be killed and displaced – Christian networks across the Holy Land are under strain and are increasingly isolated from one another.

Israeli settler attacks along roads in the West Bank keep many Palestinians from travelling at all. The numerous closures of city entrances mean a journey from Jerusalem to Bethlehem – just a few kilometres apart – involves a trip of at least 40 kilometres by road, with hours-long waits at military checkpoints.

In the Old City itself, local Palestinian Christians said they are avoiding unnecessary journeys due to the aggressive Israeli security presence in the Old City and the rest of East Jerusalem.

‘I fear Christmas is losing its spirit’

Christo commutes from the neighbourhood of Beit Hanina to open his souvenir shop in Jerusalem’s Old City, passing through Damascus Gate where border police are stationed. Before the war, Christo would not be checked often by them. “Now, daily, whenever you pass – khalas, because you’re Arab, you’re going to get fully checked,” said Christo, who wears a large, golden cross around his neck.

“And it’s terrible. Humiliating. Sometimes I don’t want to come back to the Old City.”

In one instance, a soldier stopped to give him a full body check just two metres away from where he had already been checked moments before. “He saw I was just checked,” he said. “It’s like he’s trying to make you angry to cause some problems.”

Schools have reported to the churches that students in the Old City have had their school bags checked by security forces on their way to school, looking for curriculum materials they disapprove of, including images of the Palestinian flag.

Under this economic, political, social and high-security atmosphere, the Christian community, which now comprises less than two percent of Jerusalem’s population, feels more at risk than ever. “Lots of people are thinking of [leaving], even myself,” admitted Hani. “I am not leaving here, not me, not my family. But yes, it occurred in my head.”

Enduring this moribund Christmas season – which comes amid growing violence and harassment towards local Christians, especially since Israel’s far-right government gained power last year – most Palestinian Christians declare their intention to stay, nonetheless. The churches of Jerusalem have worked together at a level not typically seen in the past, frequently releasing joint statements to condemn rounds of violence since October 7.

Their Christmas message, released on December 21, drew parallels between the birth of Jesus and the current situation. “The Blessed Virgin Mary and St Joseph had difficulty finding a place for their son’s birth. There was the killing of children. There was military occupation. And there was the Holy Family becoming displaced as refugees,” said the statement.

“Nevertheless, in the midst of such sin and sorrow, the Angel appeared to the shepherds announcing a message of hope and joy for all the world,” the statement continued.

For local Palestinians, moments of Christmas spirit this year are fleeting. “When you go to the church or light a candle or even just navigate through the Old City streets, you can see something to smile at,” said Christo. “But whenever you see the children of Gaza on the TV, or you see poverty everywhere, or people led to starvation, that will demolish all the joy inside of you.”

Amid such incredible suffering, the question persists: has Christmas become a casualty, too?

“I fear Christmas is losing its spirit in the Holy Land, and this is catastrophic,” said Asfar. “Because that spirit is peace. And when you lose that spirit, this means that you don’t have hope.”