The Navy‘s amphibious ships are not ready to deploy Marines around the world on time, a problem that has no short-term fix and degrades America’s ability to deter adversaries and reassure allies at a time when it is needed most, according to one of the Marine Corps‘ top generals.

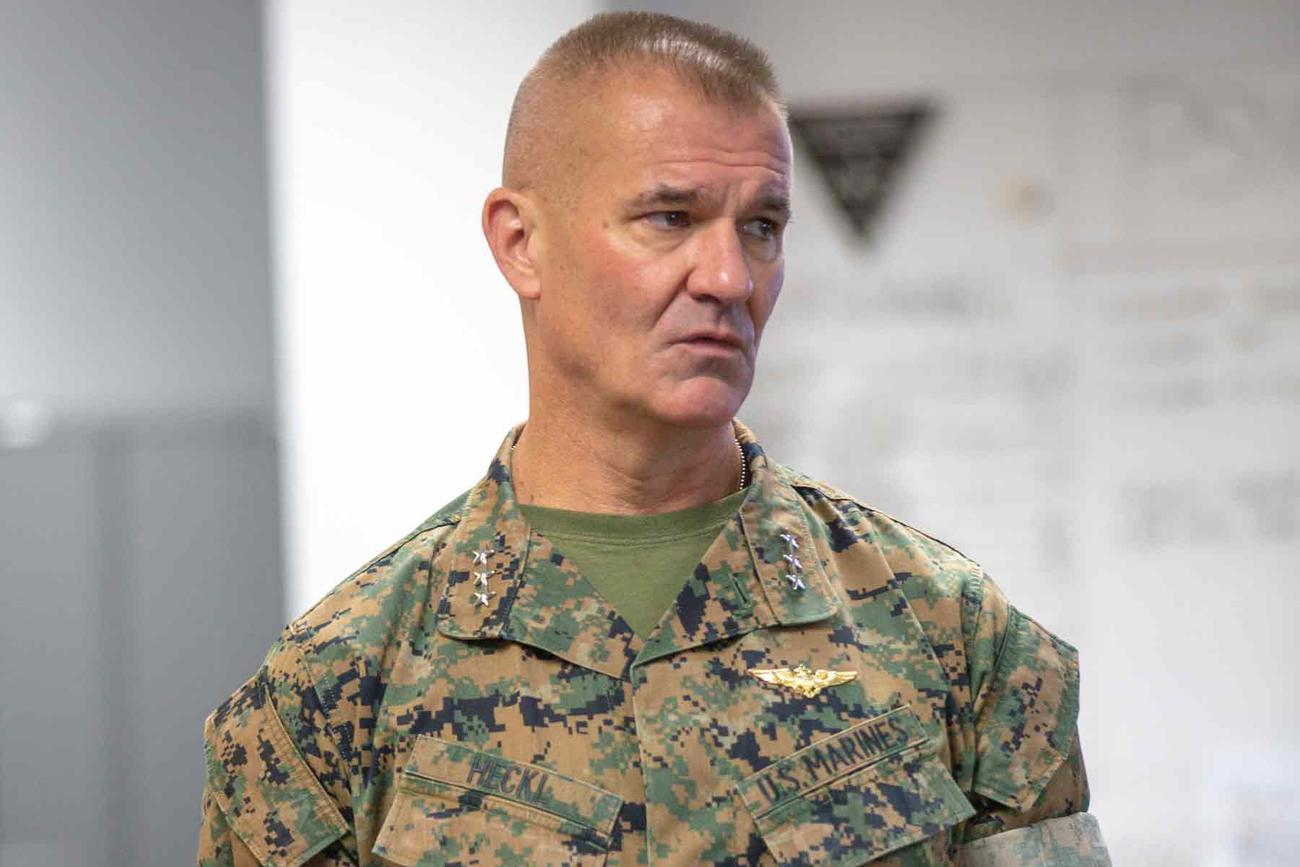

“There’s a saying that wars are a come-as-you-are game,” Lt. Gen. Karsten Heckl, the commanding general of Marine Corps Combat Development Command and deputy commandant for combat development and integration — the Marine who heads the service’s modernization efforts, told Military.com on Thursday. “Well, this is where we are. And there is simply no immediate fix.”

The readiness issue comes down to several factors, including overuse of amphibious ships during the last 20-plus years of war, according to Heckl, who said that maintenance took a back seat to the intense operational tempo that helped define the Global War on Terror. Now, according to the general, the Navy and its Marine passengers are reaping the consequences of those decisions, just as conflict in the Middle East boils over once again.

Read Next: Pandemic-Related Backlog of 600,000 Veterans Records Requests Finally Cleared

There is no good solution in sight, Heckl said, and the Corps is concerned that its expeditionary units could be in a position where they cannot meet the needs of a new crisis given the current state of the Navy’s amphibious ships, a problem it has been faced with over the last two years.

“From a defense perspective, we lose a lot,” Heckl said of the now “sporadic nature” of Marine expeditionary unit deployments, “whether it’s reassuring allies and partners or whether it’s campaigning with allies and partners to deter potential adversaries.”

The relationship between Marines and their “amphibs” is meant to be a close one. Marine expeditionary units, or MEUs — of which there are seven — deploy on those ships as one of America’s long arms of action and deterrence around the world. They are meant to be deployed with no gaps between rotations to ensure the U.S. has a rapid response force always on call, according to the Corps.

But one of those gaps meant Marines were unable to respond to an earthquake in Turkey and the evacuation of Americans from Sudan, an absence that led then-Commandant of the Marine Corps Gen. David Berger to tell Congress in a hearing in April that he felt “like I let down the combatant commander.”

Combined, the Marines and sailors deployed together make up an amphibious ready group, or ARG. That relationship is being tested amid a backdrop of renewed conflict in the Middle East and as the Navy struggles to keep a MEU afloat in the region. Marine Corps officials fear there could be a gap — of months — in coverage there because the amphibious ships their troops deploy on are not ready.

“There’s considerable, considerable, considerable, big, large — by months — gaps between the MEUs now” because of the unavailability of amphibious ships, Heckl said. “If we’re talking about months, months and months of gaps in between the crisis response force[s], we don’t have a crisis response force.”

Now, commanders in the region who are likely looking at vulnerable U.S. embassies to evacuate, for example and according to Heckl, may have to think twice about the assets they have to use, some of which continue to be strained because their replacements cannot deploy on time.

Military.com asked the Navy to respond, but it did not do so by publication.

The tension between the Navy and Marine Corps over not only the size of the amphibious fleet but its state of readiness has been an issue that has simmered away inside the halls of the Pentagon for years, often being discussed hand-in-hand with how large the Navy’s overall ship count should be.

However, the issue of amphibious ship readiness has become noticeable in part because top Marine officials have been willing to speak more openly and clearly about the issue in the past year. For example, last March, Berger told Defense One that less than one-third of the Navy’s amphibious fleet was deployable. Those assessments were also backed up by independent government investigations.

“I don’t think there’s any real, physical, tangible solution that will fix the amphib situation in the near term,” Heckl said. “We’re trying to find interim solutions, but they will not — I repeat — they will not be optimal. Whatever it is, if it isn’t an amphibious warship, it’s less than optimal and it’s less than fully capable.”

It wasn’t always this way, according to the general.

“The Navy had ships ready to go and we weren’t there,” he said, adding that because the MEUs were not ready around the 2009 or 2010 timeframe, he believes the Navy did not see them as a priority. “Now, the roles are reversed: We have the MEUs, trained and ready to go, but we don’t have the amphibious ships.”

The lack of amphibious ship availability has created significant scar tissue for the Marine Corps over at least the last two years. Heckl pointed to several examples since 2022 in which Marines were hard-pressed to respond to crises because they didn’t have a way to get there on time.

“Just look at the last couple of years — whether it was no MEU out when Russia started forming up on Ukraine’s border, to an earthquake in Turkey,” he said. “The emergency evacuation of American citizens out of Khartoum in Sudan — we had to rely on other countries. To now, with what’s happening in Israel. … Luckily, we had the crisis response force that was out, and they responded, and they’ve been there ever since.”

The specific crisis response force that Heckl is referring to is the 26th MEU out of Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, a unit that is capable of conducting special operations, port seizures and embassy evacuations. It, as part of the Bataan Amphibious Ready Group, is currently at the center of these concerns for the Marine Corps.

The 26th MEU has been deployed to the Middle East and Mediterranean since departing the U.S. in July, and at one point over the fall, was headed to the waters off of Israel in response to Hamas’ surprise attack on the country, which thrust the region into uncertainty and turmoil. According to Heckl, that unit is “looking at yet another extension” because of the amphibious ship situation.

“When you extend an ARG like that, it has a lot of ramifications, both material-wise and manpower. Material-wise, that ship is now staying underway longer than it had been planned and is probably impacting some maintenance avail[ability] that was scheduled,” Heckl said.

“And then the manpower — maintaining good faith and trust with our Marines,” he added. “What happens to those Marines that had an end-of-active-service date, and now they’re getting essentially involuntarily extended?”

Military.com previously reported that the Pentagon is weighing whether to keep the Bataan Amphibious Ready Group and the Marine Corps’ 26th MEU deployed to the area for months more as they wait for a replacement.

Last week, Navy officials stressed that they have “several options to fulfill the missions in the region” and pushed back on the idea that one amphibious ship — the USS Boxer — being unready to deploy was causing issues for the already deployed USS Bataan.

The consideration comes as a fear proliferates within the Corps that, due to delays in the amphibious ships, there will be times when Marine expeditionary units may not be deployed consecutively, damaging the Corps’ reputation as a “911” force.

“Our identity is elemental to who we are as Marines. We are soldiers of the sea. We are the nation’s naval expeditionary force,” Heckl said. “And we just can’t lose that.”

The problems are not contained to the Navy and its own internal issues. Heckl also pointed to a wavering industrial base that he says cannot keep up with the shipbuilding demand as part of the problem. The last 20 years of war, which saw back-to-back missions prioritized by leaders at the time, also left maintenance by the wayside for years, he said.

“We simply did things that I think, otherwise, we would not have done. We deferred maintenance, we extended or just delayed maintenance … on ships,” he said. “And those things — and I’m sure the leaders at the time went in eyes wide open — but they had to have known, and we certainly know now, that that comes with a price tag to be paid in the future. And we’re paying it now.”