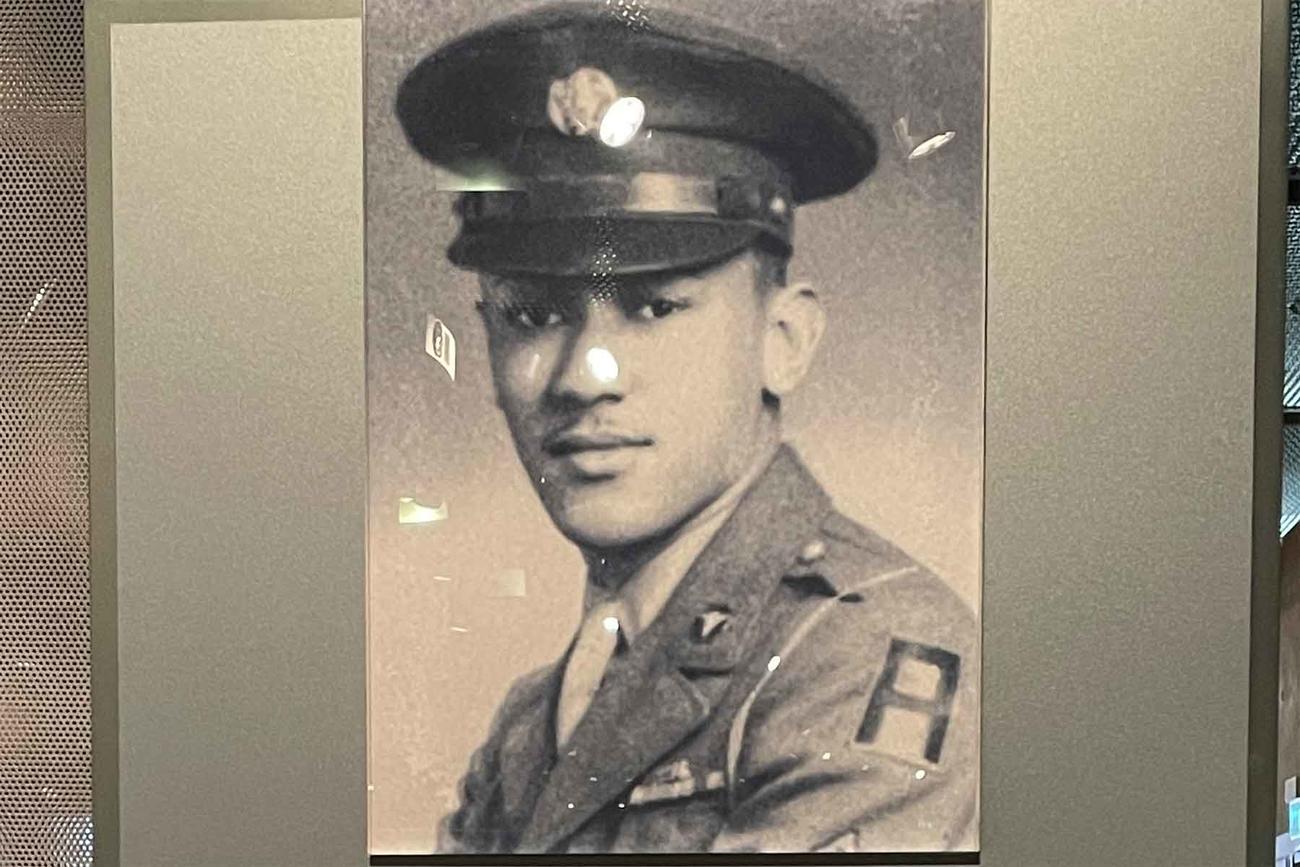

They haven’t waited in Normandy, or in smalltown Virginia, or at First Army Headquarters in Rock Island Arsenal, Illinois, to honor the D-Day heroism of then-Cpl. Waverly B. Woodson Jr., a combat medic with an all-Black unit who is under consideration for the posthumous award of the Medal of Honor.

The visitor center at the Normandy American Cemetery in Colleville-sur-Mer, France, overlooking the eastern end of Omaha Beach, now has an exhibit extolling his above-and-beyond service there with the segregated 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion in the D-Day landings on June 6, 1944.

In Bedford, Virginia, the National D-Day Memorial, originally set up to honor the 19 “Bedford Boys” who fell on Omaha Beach on the first day of the invasion, has installed a commemorative brick in tribute to Woodson and a narrative plaque on the service of the 320th.

For decades after the war, the general belief was that there were no Black units or soldiers who landed on D-Day, but the plaque notes that the 320th was “the only Black unit to land on D-Day and the only full barrage balloon unit to fight in the European theater.”

The plaque also recalls the praise for the 320th from Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, who said the unit “carried out its mission with courage and determination and proved an important element in the air defense team.”

In a phone interview with Military.com, April Cheek-Messier, president and CEO of the National D-Day Memorial Foundation, joined a growing chorus of historians, members of Congress, the U.S. First Army and the Woodson family in pressing the case for Woodson, who died in 2005, to receive the nation’s highest award for valor.

“Absolutely, he merits the award,” Cheek-Messier said. “He ignored his own wounds” on Omaha Beach and “put others above himself that day.”

Woodson’s selfless service was also the theme of a dedication ceremony in April 2022 at the Rock Island Arsenal headquarters of the First Army, which was the parent unit to which the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion was attached on D-Day.

In changing the name of the Rock Island Arsenal Health Clinic to the Woodson Health Clinic, the Army paid tribute to “a true American hero, someone whose heroism has gone unrecognized for far, far too long,” then-Maj. Gen. Chris Mohan, a senior mission commander at Rock Island Arsenal at the time, said during the ceremony.

The program for the ceremony spelled out what then-21-year-old Woodson did after landing on Omaha Beach in the first wave: ”Gravely wounded on approach — shrapnel had ripped open his thigh and buttocks — he hastily set up a first aid station on Omaha Beach and got to work.”

“He dragged the dead and wounded from the surf. He removed bullets, dispensed blood plasma, even amputated one man’s right foot. Thirty hours later, Woodson was on the brink of collapse from fatigue and blood loss when he saw three British soldiers drowning in the rough sea. He rushed to their aid and performed CPR. All survived.”

Mohan and others at the ceremony made clear their belief that Woodson was denied the Medal of Honor because of the color of his skin. ”We are righting a historical wrong” by continuing to press the case for the posthumous award of the Medal of Honor to Woodson, Mohan said. “He did not consider skin color when he was treating wounded soldiers at Omaha Beach.”

In 1994, Woodson was awarded the French Legion of Honor — the highest decoration awarded by France — on the 50th anniversary of the D-Day landings, but there was still no recognition from his own government. Then in 1997, President Bill Clinton commissioned a report on why not a single African American who served in World War II had been awarded the Medal of Honor.

The result was that seven African Americans were awarded the Medal of Honor — six of them posthumously — but the case for giving the award to Woodson was rejected. Review boards place great weight on eyewitness corroboration to make the award, and witnesses were lacking to back up what Woodson did on June 6, 1944.

Records that might have supported the award for Woodson also were lost in the 1973 St. Louis fire at the National Personnel Records Center that destroyed millions of military documents. There the matter rested until 2016 with the publication by journalist and author Linda Hervieux of the groundbreaking book “Forgotten: The Untold Story of D-Day’s Black Heroes, at Home and at War.”

Woodson “wasn’t even given the combat medic’s badge” because of “systemic racism in the Army” at the time, Hervieux told Military.com, but her persistent research led to the Truman presidential library in Independence, Missouri, where she found evidence that the argument for awarding the Medal of Honor to Woodson had reached the White House of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The evidence was in the form of a memo from Philleo Nash, a deputy director in the Office of War Information, to Jonathan Daniels, a special assistant to Roosevelt, alerting Daniels to the possibility that Woodson was owed a major award.

If the relevant authorities in Europe would speed up their reviews, “we would soon know whether he [Woodson] will get a Congressional Medal of Honor,” as the Medal of Honor was known at the time, Nash wrote. “This is a big enough award that the president can give it personally, as he has in the case of white boys.”

Capt. Kevin Braafladt, a First Army historian, said that an Army press release detailing Woodson’s actions on Omaha beach was attached to the Nash memo. “There was a conscious effort taking place here. They were trying to get him the Medal of Honor,” Braafladt said, but “we suspect Woodson was overlooked for racial reasons.”

Hervieux’s book triggered bipartisan efforts in Congress led by Sen. Chris Van Hollen, D-Md., who introduced a bill calling for Woodson to receive the Medal of Honor that drew tentative support from the Trump White House.

Then-White House spokesman Judd Deere said that “President Trump believes Cpl. Waverly Woodson, like all of those who have bravely served, is a hero,” and Trump “is inclined to support the legislation to honor Cpl. Woodson,” according to a September 2020 Washington Post article.

The bill, H.R. 8194, failed to receive a vote on the House side, but Van Hollen kept the issue alive before a Pentagon review board for Woodson, who was discharged as a staff sergeant.

In a statement to Military.com, Van Hollen said that Woodson “displayed extraordinary valor on D-Day” but “his heroic actions never received the full recognition they merited, due to the color of his skin. It’s overdue that we right past wrongs and award Staff Sgt. Woodson with the Medal of Honor — a recognition he so clearly earned.”

Van Hollen joined Woodson’s widow, 94-year-old Joann Woodson, and his son, Stephen Woodson, at Woodson’s gravesite in Arlington National Cemetery on Oct. 11 for a ceremony in which Woodson finally was posthumously awarded the Bronze Star and Combat Medical Badge he had earned on D-Day but never received.

The Army’s release announcing where and when the ceremony would take place was unusual in the sense that it appeared to be laying out the case for Woodson to receive the Medal of Honor.

The release said that Woodson was “an African American medic who served heroically during the WWII D-Day invasion and who is currently at the center of bipartisan congressional efforts to upgrade him to the Medal of Honor.”

Under the heading “Additional Information,” the Army noted Hervieux’s book and cited Braafladt’s work to uncover “a trove of previously undiscovered evidence that Woodson was actually nominated for the medal during WWII, but the award was thwarted due to racism, lost records and infighting among senior leaders in the European theater.”

At the graveside ceremony, retired Army Lt. Gen. Thomas James, who has lobbied for Woodson to receive the Medal of Honor and written op-eds to that end, described what it must have been like for Woodson in the chaos of Omaha Beach.

“Imagine the unforgiving crucible of ground combat,” James said. “The explosions, the hail of bullets, machine-gun fire, artillery rounds, the smoke, the blood, the sweat. And then you hear that familiar cry: ‘Medic! Medic!’ From the explosions, smoke and hail of bullets runs a young corporal, Cpl. Waverly Woodson, with an aid bag.”

Steve Woodson said it was not a surprise to hear that his father risked his own life to come to the aid of others. “One thing about my Dad that I will always remember was his care for other people, and it did not matter the race of the person.”

In a later interview with Military.com, Steve Woodson said it was a surprise on a recent trip to Normandy to find that many of the French knew about his father and the efforts to secure for him the posthumous award of the Medal of Honor.

He took in the exhibit on his father and the 320th at the Colleville-sur-Mer museum. “It was unbelievable to walk on that beach” where his father struggled to aid the wounded, Steve Woodson said.

His mother also walked on Omaha Beach with her husband in 1994, the 50th anniversary of D-Day, when the government of France awarded Woodson the Legion of Honor.

Joann Woodson told ABC News in 2015 that, as they approached the beach, her husband “walked along and would look out over the water. He told me the noise was deafening that morning. He said, ‘My buddies are gone,'” Joann Woodson said. “All the memories surfaced. I asked him, ‘Are you sure you want to continue down the beach?’ He said, ‘Yes.’ I held his hand, and he and I walked down the beach.”

Editor’s note: Richard Sisk is a former colleague of Linda Hervieux. Both worked at the New York Daily News.

— Richard Sisk can be reached at Richard.Sisk@military.com.

Related: Cobra Pilot Who Lifted Troops to Safety in Vietnam Is Awarded Medal of Honor at White House Ceremony