Islamabad, Pakistan – It is often tempting to declare every election as the most significant in a country’s history. But when Pakistan goes to polls on Thursday – in what some critics warn may be the most unfree election to date – it is no hyperbole to say the stakes are enormously high.

Former Prime Minister Imran Khan languishes in jail as the authorities crack down on his Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party, while previously imprisoned and exiled former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif is back to contest the vote alongside an array of other candidates from the left to the right.

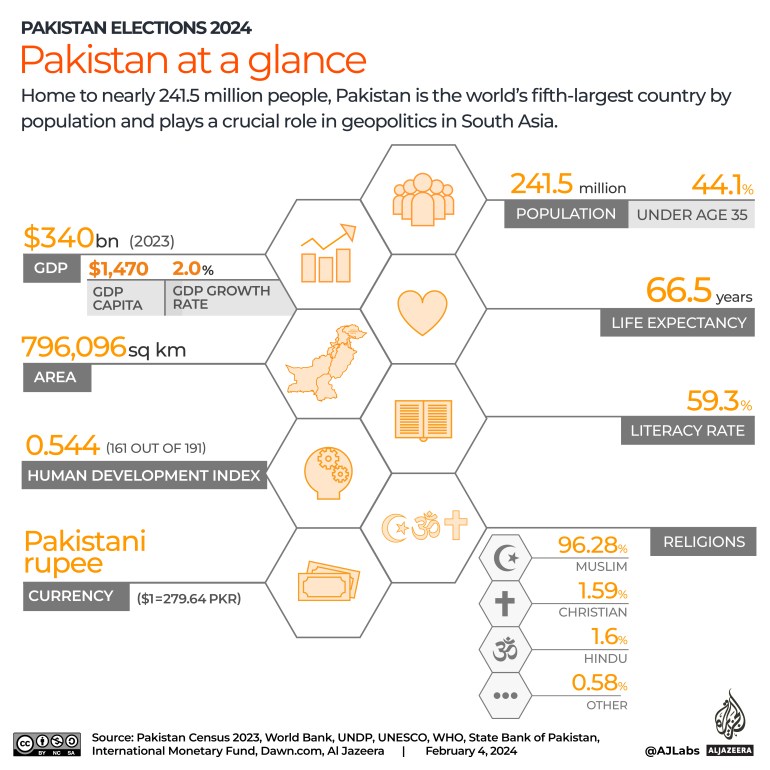

However, the focus of this election is not only on addressing nearly two years of political instability but, crucially, on establishing a new, steadfast government that can stabilise an economy in crisis for Pakistan’s 241 million people.

Some 40 percent of the population lives below the poverty line, inflation has skyrocketed to more than 30 percent, and according to a poll released this week, about 70 percent of Pakistanis believe economic conditions are worsening.

Last June, Pakistan faced the imminent threat of default, with foreign reserves plummeting to $4.4bn – barely covering a month’s worth of imports – while the currency shed more than 50 percent of its value against the United States dollar.

As the country found itself at a precarious juncture, then-Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif managed to secure a crucial bailout package from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – its 23rd fund programme since 1958 – just weeks before the government’s term expired.

The interim government, assuming power in August 2023, confronted the primary challenge of ensuring the continuity of the IMF programme, valued at $3bn.

Spanning nine months, this Standby Arrangement (SBA) IMF deal necessitated tough measures, including the elimination of subsidies on essential commodities, and allowing the rupee value to be determined by the open market.

With the current IMF programme concluding in March, just as the new government will take power, analysts emphasise that the winning party’s first order of business must be to re-enter negotiations with the global lender to maintain stability.

Simultaneously, Pakistan faces a looming debt payment crisis, with the central bank reporting $24bn of external debt obligations due by June 2024.

‘Anti-populist’ steps

The incoming government needs to negotiate with the IMF for a new programme, while also taking steps to reduce expenses and balance the budget deficit, Karachi-based economist Asad Sayeed emphasises.

“The government has to continue to take steps which are anti-populist in nature, subsidies on gas and petroleum cannot be resumed, exchange rate cannot be manipulated, and the focus should be to reduce expenses and balance the budget deficit,” Sayeed, who is a director at the research firm Collective for Social Science Research (CSSR), told Al Jazeera.

Sajid Amin Javed, a senior economist associated with the Sustainable Development Policy Institute in Islamabad (SDPI), urges the incoming government – regardless of its political affiliation – to prioritise economic decisions over political considerations and immediately engage with the IMF.

“The new government must keep politics separate from economics. They must avoid populism-driven decisions which were taken by some of its predecessors,” Javed told Al Jazeera.

The urgency conveyed by economists underscores the critical state of Pakistan’s $340bn economy amid a volatile political landscape.

The recent history of economic challenges includes Pakistan entering a $6bn, 39-month-long IMF bailout programme in 2019.

In early 2022, then-Prime Minister Khan’s decision to reduce fuel prices amid global spikes due to the Ukraine-Russia war violated IMF requirements, leading to challenges for the subsequent government.

Khan’s government was deposed in April 2022, replaced by a coalition government formed under the banner of the Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM) – an alliance that also includes Sharif’s Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PMLN) party.

In August 2022, the PDM government resumed the IMF programme but soon replaced the finance minister, Miftah Ismail, with a two-time former finance minister, Ishaq Dar.

However, economists have argued that Dar’s attempts to control the exchange rate has had adverse effects on the economy, similar to the PTI government’s decision to cut petrol prices.

Economist Sayeed said one of his concerns with the government of the PMLN – the frontrunners in the election – was if they bring back the same economic policies that were pushed by Dar, who is a senior member of the party.

“If the PMLN wins a simple majority and come in [to] power, they can end up taking steps which may derail the already delicately placed economy. You will again be teetering on the edge of a crisis and a potential default,” he said.

Tackling inflation

Additionally, the impact of inflation over the past year and a half is another pressing issue, which has led economists to underline the incoming government’s need to recalibrate its priorities.

Islamabad-based economist Javed warned that the wrong policies could jeopardise the delicately balanced economy, potentially leading to a crisis and default.

“Tackling inflation and protecting people from side effects of stabilisation policies must be top priority,” he said.

“The people, particularly the poor, have suffered a lot. Prolonged higher inflation and unemployment have pushed many below the poverty line. They need to be supported.”

Ali Hasanain, an associate professor of economics at Lahore University of Management Sciences, highlighted the enduring challenge of balance-of-payment crises throughout Pakistan’s history.

“There is no decade in which we have not stumbled through a balance-of-payment crisis and suffered ‘sudden stops’ in our economic management, accompanied by rapid, unplanned devaluations of the rupee and a painful spike in the costs of living,” he told Al Jazeera.

Highlighting the country’s plight, Hasanain said Pakistan is required to pay nearly $90bn in external debt obligations in the next three years.

These liabilities require the country to repay more every year than what it received, $60bn, in China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) investment in a decade.

“The government badly needs a plan to tackle this fact. But since this appears almost certainly infeasible, we need to negotiate with our lenders, either through a restructuring of our debt, or through offering equity in Pakistani assets,” he added.

Roadmap ahead

Fahd Ali, an assistant professor of economics from Lahore University of Management Sciences anticipated the incoming government struggling to align campaign promises with the reality of a sluggish economy.

“The party manifestos of leading parties promise lavish spending. This would be a tough promise to keep given that it is likely the new government will have to sign another three-year agreement with the IMF,” he told Al Jazeera.

Javed from SDPI underscored the need for any government to outline a plan for the first 100 days, with a focus on expanding the tax net. The tax-to-GDP ratio, currently at 10.4 percent, is among the lowest in the Asian region.

Economist Sayeed stressed the importance of policymakers helping the country move away from its longstanding “consumption-based growth model”.

The latest Pakistan Economic Survey in June 2023 (PDF) revealed that consumption expenditure accounted for almost 94 percent of the country’s GDP, while investment’s share remained more than 13 percent.

However, Sayeed contended that the most imminent threats faced by Pakistan are the challenges and effect of climate change and climate-induced disasters.

Recalling the floods of “biblical proportions” just two years ago, he emphasised the need for significant investment in climate mitigation and adaptation strategies.

“Climate-related disasters are taking place every year and we need significant investment for climate mitigation and adaptation strategies and policies,” he said.

We have to seek investment in this sector, but for that, the issue itself needs to be recognised and acknowledged first.”