Ogoja, Nigeria – Rebecca stares down her sandy street past the palm trees and T-junction. No sign of Blessing. It is already after 7:30am, and their school’s morning assembly will soon start. Rebecca sighs with relief when she sees her friend running towards her. “Sorry, sorry,” Blessing gasps, “I had to queue for hours to get water this morning.” The two 15-year-olds hug and quickly make their way to their secondary school, a stone’s throw from Rebecca’s home in Ogoja, a town in southeastern Nigeria about 65km (40 miles) as the crow flies from the Cameroonian border.

The best friends sport similar buzz cuts and wear the same white blouse and navy blue skirt uniform. As they hurry to school while chatting in Pidgin, there is little to suggest that they come from different countries. Yet Rebecca Jonas was born and raised in Nigeria, while Blessing Awu-Akat is a refugee whose family fled violence in Cameroon’s Anglophone regions where Francophone government forces are fighting English-speaking separatists.

Rebecca’s family lives in town in a duplex with a gas stove and indoor bathrooms. Blessing lives in Adagom I, a settlement on the outskirts of Ogoja where almost 10,000 Cameroonian refugees reside. Her family uses firewood to cook and shares latrines and showers with other refugees. And in the morning, when everybody is waking up, she has to wait in line to use the communal water taps to wash and collect water to prepare breakfast. Which is why Blessing’s friend cuts her some slack when she is late.

An open settlement

Blessing’s family fled to Nigeria in November 2017. She remembers the morning when an army helicopter suddenly hovered over their village of Bodam, which lies close to the Nigerian border. “Everyone started running into the bush. But there, soldiers were shooting at people,” she recalls.

A friend of hers was shot, Blessing says, shivering in horror as she points at where the bullet shattered her friend’s arm. She, her parents, her three siblings and two cousins, escaped on foot to the Nigerian border unharmed, but destitute. “There was no time for us to pack. All I had was the dress I wore that day.”

Just across the border, the violence was never far away, and at night, gunshots on the Cameroonian side kept the then nine-year-old girl awake. Because the border area was not safe for the thousands of refugees, Nigerian authorities decided to move them further inland. This is how Blessing’s family was resettled at Adagom I, 63 hectares (156 acres) of federal government land that Nigeria offered to the United Nations refugee agency UNHCR to use as a settlement for the refugees. “Here I finally managed to sleep through the night,” Blessing says.

Adagom I, named after the village in the Ogoja area where the refugees were resettled, is not a refugee camp with curfews, exit restrictions and separate camp schools and clinics, but an open settlement of about 3,000 households where inhabitants can come and go as they please and interact with their Nigerian neighbours freely. In Nigeria, a country already faced with the challenge of more than two million internally displaced people (IDPs), mostly in the northeast, all 84,030 UN-registered refugees from Cameroon enjoy freedom of movement, access to healthcare, education and the right to work – rights that many wealthier countries in the world do not immediately grant to foreigners seeking refuge within their borders.

The government also waived school fees for refugee children to enable them to continue their education and return to as normal a life as possible. That is how Blessing and Rebecca became classmates and best friends at Government Technical College, Ogoja.

Knowing what it’s like to be new somewhere

Blessing and Rebecca barely make it to the school assembly on time; the band has just started playing the school anthem as they rush through the wrought iron gate. When the assembly is finished, they head to their classroom, where they always sit together, preferably at the front. As they wait for their English lesson to start, they recount how their friendship started.

It was Blessing who welcomed Rebecca on the first day she came to school in March 2021. Rebecca had just moved from Lagos with her mother and brother – her father stayed behind to run his business selling home appliances. She dreaded her first day in a new school. But there was Blessing, a friendly girl who had attended the school since her family arrived in Ogoja in September 2018. She greeted the more timid Rebecca when she entered the classroom and moved over to make space for her to sit down.

“She was the first to accommodate me,” Rebecca says with a smile. “She knew how it was to be completely new somewhere.” After school, it turned out, they took the same route home, and since that first day, Rebecca has waited for Blessing to pass by her house in the mornings so they can walk to school together.

Rebecca is aware that violence drove her friend out of her country, but she does not ask her about it. “I don’t want to make her cry,” she says.

Sometimes, she sees sadness in Blessing’s eyes, and her chatty friend grows quiet. Then Rebecca tries to cheer her up by telling her a silly story or getting her to sing – they love to sing gospel songs together. Sometimes, she notices Blessing finds it hard to concentrate in class. “Then I know that afterwards, she’ll be asking to take my notes home to copy them,” she says. Even though it means she won’t be able to study that day, Rebecca says, “I have to lend her what I can. She’s my friend.”

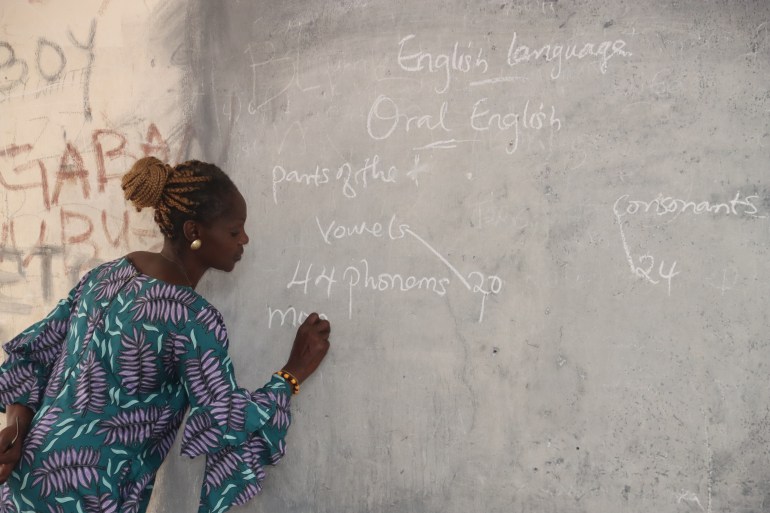

Their English teacher Comfort Ullah Solomon, 46, remembers how lost and lonely many of the refugee students appeared when they first arrived in Ogoja. “They seemed miles away, sometimes they were not even listening, as if they were in a trance,” she recalls. When Adagom I opened in 2018, a lot of Cameroonian children came to the school. In the first year, almost one-third of the students were from Cameroon. Today, as they have moved to other schools in Ogoja, about 150 of the more than 1,000 pupils of the secondary school are Cameroonian.

Sometimes, in those early days, there was friction, the teacher says. She describes an incident where a Nigerian and Cameroonian student were running around when the former playfully shouted, “I will shoot you!” The Cameroonian teenager broke down, leaving his classmate puzzled. Comfort sat down with them and explained to the Nigerian pupil the violence his classmate had fled, and how for him the game might have felt real. “They became friends,” she says.

She made an effort to comfort the new students. “I kept them close, told them they were worthwhile. After a while, their absent-mindedness disappeared.”

Blessing confesses she was scared when she first arrived at her new school. “I thought the Nigerians would bully us and ask us what we are doing in their land,” she recalls. But the way the school teamed up the refugees with their Nigerian fellow students for the Friday quizzes and debate teams quickly made her feel accepted.

Her 17-year-old Nigerian classmate, Benjamin Udam, admits he was also worried when the new students came. “I thought maybe they had a different way of life than us. But we turned out to be just the same,” he says.

Blessing’s Nigerian classmate Alice Abua, 16, remarks that Cameroonians prepare their soup with very little water, another mentions they dance the makossa, while another suggests their English sounds a little different. Apart from that, they don’t see any substantial differences between Nigerians and Cameroonians. And when asked who has a friend from the other country, everyone in the classroom raises a hand.

Rice and beans

After school, Rebecca joins Blessing at her place to cook rice and beans, their favourite meal. They stroll to the settlement market to buy condiments, over the red sand paths lined with papaya, palm and mesquite trees, past the one-storey houses refugee families built with bricks and roofing sheets provided by the UNHCR.

The market vendors are a mix of refugees and locals. Janet Aricha, the woman the girls usually buy crayfish from, is from Ogoja. She never saw the refugees as a threat. “I felt bad for them,” she explains. “Imagine to lose your home and everything in a single day.”

Much like the other Nigerian sellers at the market, she saw the influx of new customers as a business opportunity. Even in town, most people agree that economic opportunities in Ogoja, home to an estimated 250,000 people, grew with the arrival of Cameroonian refugees.

Meanwhile, the girls realise the money Blessing’s mum gave them has finished before they have managed to buy all the ingredients they need. “How did we forget pepper?” Rebecca asks her friend in disbelief. But Blessing has a solution; on the way back, she asks a neighbour if she could pluck some chillies from their garden.

At home, Blessing’s mother has started the fire. While her daughter and her best friend prepare the meal, Victorine Ndifon Atop talks about life in this new place.

It’s not easy, but for the children she tries to make life as familiar as the one they left behind, the 43-year-old says. She points at the garden in front of the 20-square-metre (215-square-foot) house the now family of nine shares. The small patch of lawn is meticulously cut and the white periwinkle and hibiscus shrubs are blooming.

She only knew Nigerians from Nollywood movies when they first came to Nigeria. “In those movies, they are always shouting at each other,” she says. “So back home, we thought they were all ruffians.” But six years in Adagom I changed her mind. When the refugees first arrived, complete strangers from town brought them clothes and provisions. And one day, a Nigerian neighbour from the host community of Adagom gave her a plot of land she now grows cassava on to prepare fufu, a popular Western African dish, to sell. “They embraced us and received us like family,” she says.

‘They are like us’

Down the road, a five-minute walk away, Adagom I chief Stephen Makong shrugs to indicate he finds his community’s hospitality towards refugees self-evident. “Of course, we gave them land to farm on. If you don’t, what are they going to eat?” he asks.

When the village leader was told about the refugee settlement plan in his community, he saw it as a blessing. “My father taught me: for strangers to come to your house, you must be a good person.” Not everyone in his community thought so, he adds. “Some young men were afraid they would come and claim ownership of the land. But I told them they did not come to steal our land. They are running from war. You cannot drive them away again.”

But there are occasional disputes. “Even when two brothers live in a house, they quarrel,” the chief says. When some refugees cut trees in the forest for firewood, a town hall meeting was called to explain that in Cross River State you only use deadwood for cooking. But life together has been largely harmonious, most people in the village say. They have also benefitted from the settlement’s development. The UNHCR divides investments in the local infrastructure between the refugee and host community, reserving about 30 percent of its budget for the latter. The drilled wells, water taps and the widened road through the village wouldn’t be there if it weren’t for the refugees.

On top of that, the locals discovered that some Cameroonians are from the same ethnic group as them – the Ejagham who live on both sides of the border. So they even share a language, says Makong. “They are like us. We are the same people.”

That cultural proximity, combined with the perceived economic advantages, could explain why Ogoja has taken in thousands of Cameroonians without much local resistance. Farmers who used the federal land where the refugees were settled may grumble a bit even though they have been compensated for the crops they could not harvest. And with inflation making everyone’s money far less valuable, the town’s economic activity has ground to a halt, much like in the rest of the West African country. But that does not make the refugees less welcome, says the chief. “We enjoy together, and we suffer together.”

This hospitality towards strangers on the run from violence is not an exception in Nigeria. Three-quarters of the Cameroonians seeking refuge in the country did not have to go to a refugee settlement – they found shelter within a community. Just as, according to the UN, more than 80 percent of Nigerian IDPs found refuge with fellow Nigerians.

‘She is my friend’

Back at Blessing’s home, the two girls have finished cooking and sit in the shade with a plate of steaming rice topped with smoky bean sauce on the floor in front of them. For a while, the chatting stops and the only sound is the clicking of two spoons on the shared aluminium plate. When they finish their meal, Blessing teases her slender friend, “The way you eat! I don’t understand you’re not fatter.”

The sun is on its way down when Rebecca arrives back home, but her mother does not mind. She is happy her daughter has found such a good friend. “When I look at them, they remind me of my best friend and me back home in Akwa Ibom,” says 39-year-old Favour Jonas, referring to the Nigerian state she grew up in. “I remember how we used to gist, play and sing together as girls.”

Next year will be the girls’ final year in secondary school. Afterwards, even if they go to different universities, Rebecca is sure they will stay in touch. For now, she has more immediate things to think about. Tomorrow they have a maths and an economics exam, and Rebecca hopes Blessing won’t be late. But even if she is, she will wait for her. “I have to,” she says. “She is my friend.”

This article has been produced with the support of UNHCR.