Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, December 29, 2023

Christina Harward, Riley Bailey, Angelica Evans, Karolina Hird, and Frederick W. Kagan

December 29, 2023, 6:35pm ET

Click here to see ISW’s interactive map of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This map is updated daily alongside the static maps present in this report.

Click here to see ISW’s 3D control of terrain topographic map of Ukraine. Use of a computer (not a mobile device) is strongly recommended for using this data-heavy tool.

Click here to access ISW’s archive of interactive time-lapse maps of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. These maps complement the static control-of-terrain map that ISW produces daily by showing a dynamic frontline. ISW will update this time-lapse map archive monthly.

Note: The data cut-off for this product was 12:30pm ET on December 29. ISW will cover subsequent reports in the December 30 Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment.

Russian forces conducted the largest series of missile and drone strikes against Ukraine since the start of the full-scale invasion on the morning of December 29. Ukrainian military sources reported that Russian forces launched 36 Shahed-136/131 drones and over 120 missiles of various sizes at industrial and military facilities and critical infrastructure in Kyiv, Kharkiv, Lviv, Dnipro, Zaporizhzhia, and Odesa cities and Sumy, Cherkasy, and Mykolaiv oblasts.[1] The Ukrainian General Staff reported that Russian forces launched a total of 160 projectiles at Ukraine and that Ukrainian forces downed 27 Shaheds and 88 Kh-101, Kh-555, and Kh-55 missiles.[2] Ukrainian Commander-in-Chief General Valerii Zaluzhnyi reported that Russian forces first launched the 36 Shahed drones from the northern, southeastern, and western directions in the early hours of December 29.[3] Zaluzhnyi reported that Russian strategic aircraft and bombers later launched at least 90 Kh-101, Kh-555, and Kh-55 cruise missiles and eight Kh-22 and Kh-32 missiles.[4] Russian forces also struck Kharkiv City with modified S-300 air defense missiles and launched a total of 14 S-300, S-400, and Iskander-M ballistic missiles from occupied Crimea and Russia.[5] Zaluzhnyi reported that Russian forces also launched five Kinzhal hypersonic air-launched ballistic missiles, four Kh-31P anti-radar missiles, and one Kh-59 cruise missile at unspecified targets in Ukraine.[6] Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky reported that Russian forces struck civilian infrastructure such as a maternity hospital, educational institutions, a shopping center, a commercial warehouse, and residential buildings in cities throughout Ukraine.[7]

The strike package that Russian forces launched on December 29 appears to be a culmination of several months of Russian experimentation with various drone and missile combinations and efforts to test Ukrainian air defenses. Over the past several months, Russian forces have conducted a series of missile and drone strikes of varying sizes, using various combinations of drones, cruise missiles, and ballistic missiles.[8] In most of the more recent strikes, Russian forces notably used either exclusively Shahed-136/131 type drones or a majority of Shahed drones accompanied by a smaller number of missiles.[9] In contrast, the December 29 strike package included 36 Shahed drones and 120 missiles of various sizes.[10] Ukrainian military officials, including Ukrainian Air Force Spokesperson Colonel Yuriy Ihnat, have long noted that Russian forces frequently use Shahed-type drones to probe Ukrainian air defense and determine what strike routes most effectively circumvent Ukrainian air defense clusters.[11] Ukrainian Main Military Intelligence Directorate (GUR) Deputy Chief Major General Vadym Skibitskyi also notably assessed on August 28 that Russian forces were likely employing strike packages comprised of more drones than missiles in order to determine flight paths that bypass Ukrainian air defenses and allow other projectiles to more reliably reach their intended targets.[12] ISW assessed on October 21 that Russian forces were likely diversifying the mix of missiles, glide bombs, and drones used in strike packages in order to determine weaknesses in Ukrainian air defense coverage to optimize a strike package such as the one that Russian forces launched on December 29.[13] Russia was likely deliberately stockpiling missiles of various sizes through the fall and early winter of 2023 in order to build a more diverse strike package and apply lessons learned over the course of various recent reconnaissance and probing missions—namely using Shahed drones to bypass Ukrainian air defenses while utilizing missiles to inflict maximal damage on intended targets.[14] Ukrainian forces notably did not intercept any of the Kh-22/Kh-32 missiles, ballistic missiles (S-300s and Iskander-Ms), Kinzhal hypersonic air-launched ballistic missiles (Kh-47s), Kh-31P anti-radar missiles, or Kh-59 cruise missiles that Russian forces launched on December 29, which suggests that Russian forces have been able to successfully apply some lessons learned about effective strike package combinations and that the Shaheds that preceded the missiles may have distracted Ukrainian air defenses or otherwise enabled the strike.[15]

Russia will continue to conduct strikes against Ukraine at scale in an effort to degrade Ukrainian morale and Ukraine’s ability to sustain its war effort against Russia. Zaluzhnyi stated that Russian forces targeted critical infrastructure and industrial and military facilities in Ukraine on December 29.[16] Ukrainian officials indicated that Russian forces primarily struck residential buildings, transportation infrastructure, and industrial facilities, although this is not a comprehensive list of the Russian target set.[17] Russian sources, including the Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD), claimed that Ukrainian defense industrial base (DIB) facilities and Ukrainian military infrastructure were the primary targets.[18]

Russian forces conducted an initial mass strike campaign in fall 2022 and winter 2022-2023 against Ukrainian energy infrastructure that was aimed at collapsing the Ukrainian energy grid during winter to degrade Ukrainian morale to the point of breaking the Ukrainian will to fight.[19] That effort failed, but Russian forces have conducted a consistent strike campaign in Ukraine that is still aimed at degrading Ukrainian morale and have also focused on inflicting compounding costs on Ukraine.[20]

Ukraine has pursued a concerted effort to expand its defense industrial base (DIB) in the past year, and the reported Russian strikes against industrial facilities likely mean to prevent Ukraine from developing key capacities to sustain operations for a longer war effort.[21] Ukraine has also sought Western partnerships for joint production in Ukraine, and Russian strikes on industrial facilities likely aim to increase risks for Western partners and companies above their current risk tolerance for operating in Ukraine.[22]

Russian forces will likely conduct intensified strikes in the coming days to coincide with the New Year Holiday as they did last year in an effort to degrade Ukrainian morale.[23] Russian forces may still decide to strike Ukrainian energy infrastructure at scale in the coming months, although ISW still assesses that a Russian effort to break Ukraine’s will to fight is very unlikely to succeed. Russian forces likely also intend for strikes on residential areas to stir up societal discontent in connection with routine information operations that aim to exploit and amplify Ukrainian social tensions.[24]

Current Russian missile and drone reserves and production rates likely do not allow Russian forces to conduct regular large-scale missile strikes, but likely do allow for more consistent drone strikes, which can explain the recent pattern of Russian strike packages. Ukrainian Main Military Intelligence Directorate (GUR) Deputy Chief Major General Vadym Skibitskyi stated on November 6 that Russian forces produced 115 long-range high-precision missiles in October 2023, including 30 Iskander-M cruise missiles, 12 Iskander-K cruise missiles, 20 Kalibr cruise missiles, 40 Kh-101 cruise missiles, 9 Kh-32 cruise missiles, and 4 Kinzhal ballistic missiles.[25] Skibitskyi also stated on November 6 that Russian forces had a total of 870 high-precision operational-strategic and strategic missiles in reserve in November and that this number increased by 285 missiles between August and November. Although Ukrainian officials have recently stated that Russian forces have partially restored their cruise missile stockpiles, Skibitskyi’s statements about recent Russian missile reserve totals and monthly production rates indicate that Russian forces are unable to sustain repeated large-scale missile strikes comparable to the December 29 strike series.[26] The December 29 strikes, which included five Kinzhal missiles, for example, used roughly one month’s worth of Russia’s reported production of that system. Russia is able to domestically produce Shahed-136/131 drones at a much higher rate, however, largely due to the creation and expansion of the drone production facility in the Alabuga Special Economic Zone in the Republic of Tatarstan.[27] The Institute for Science and International Security reported on November 13 that even after a one-month delay in production the Alabuga facility planned to produce 1,400 Shahed-136 drones between February and October 2023 and plans to produce a total of 6,000 drones by September 2025.[28] Russian forces will therefore likely be able to conduct more consistent Shahed strikes than missile strikes, as Ukrainian officials have previously indicated.[29]

The Kremlin’s efforts to sufficiently mobilize Russia’s defense industrial base (DIB) in support of its wartime objectives, including large-scale strike series, may been more successful than Western officials previously assessed due in part to Russia’s ability to procure military equipment from its partners and the redistribution of Russia’s resources for military production purposes. Head of the German Ministry of Defense’s Special Staff for Ukrainian Issues Major General Christian Freuding stated during an interview on December 29 that the German Armed Forces did not expect that Russia would succeed in expanding its DIB and increasing its production capacity in the face of Western sanctions.[30] Freuding stated that Germany did not account for Russia’s ability to circumvent Western sanctions by procuring materiel from North Korea, China, and other countries.[31] Ukrainian outlet Ekonomichna Pravda, citing data from Forbes, reported that Russia’s December 29 strike cost Russia at least $1.27 billion, calculating that Russia spent over $720,000 to launch 36 Shahed-136/131 drones, over $5 million to launch five Kh-47 hypersonic missiles, and an estimated $1.17 billion on the over 90 Kh-101 missiles that it launched.[32] Forbes previously reported that Russian Kh-101 cruise missiles cost an estimated $13 million per missile compared to Kh-22 missiles that cost an estimated $1 million each and Iskander-M ballistic missiles that cost roughly $3 million each.[33] Russian forces notably appear to be using larger quantities of the more expensive Kh-101 cruise missiles to overwhelm Ukrainian air defenses and increase the chances of striking targets in Ukraine with smaller quantities of cheaper missile variants.

Russian opposition outlet Meduza estimated on December 29 that Russia’s economy will most likely grow by more than three percent by the end of 2023, largely due to the Russian DIB’s unprecedented levels of production that have bolstered Russian economic output.[34] Meduza, citing the Bank of Finland’s Institute for Emerging Economies, reported that Russia’s DIB generated 40 percent of Russian GDP growth in the first half of 2023 despite only accounting for six percent of Russian GDP.[35] Meduza credited the success of the Russian DIB to Russia’s significantly increased, and still increasing, defense budget and the redistribution of Russia’s civilian sector resources for military production purposes.[36] Meduza highlighted Russia’s Tambov Bakery, a bakery that began assembling 230 to 250 combat drones per month in March 2023, as an example of the Russian economy’s redistribution of money and resources towards military over civilian goods.[37] Meduza noted that the Russian DIB is unlikely to generate the same levels of economic growth in 2024, largely due to personnel shortages, already stretched production capacities, and its dependence on imported components and equipment.[38]

Russian forces have likely routinely attempted to draw and fix limited Ukrainian air defense systems away from the front, and the Russian strikes on December 29 follow recent indications that Ukrainian air defenses may be presenting significant challenges to Russian aviation operations along the frontline. Ukraine lacks the number of air defense systems required to provide even coverage to all of Ukraine, and Russian forces have likely conducted a consistent series of strikes, even if at a low intensity, in part to force Ukrainian forces to concentrate those air defense systems on protecting larger population centers far from the front instead of providing coverage for military operations.[39] Russian forces reportedly decreased their aviation activity after Ukrainian forces shot down three Russian Su-34s in southern Ukraine between December 21 and 22, which was subsequently followed by a notable decrease in the tempo of Russian ground operations on the east (left) bank of Kherson Oblast.[40] Russian forces had been relying on the mass use of glide bombs dropped from manned aircraft to support operations in Kherson Oblast and in eastern Ukraine, likely due to the reported Ukrainian ability to suppress long-range Russian artillery and shoot down Russian rotary wing aircraft.[41] A Ukrainian capability to suppress Russian aviation activity even in limited areas of the front would likely pose significant operational constraints on Russian forces.

Ukrainian forces have recently expanded their use of mobile air defense strike groups in an effort to avoid expending air defense missiles on routine Russian strikes with Shahed-136/131 drones.[42] The recent months of Shahed-heavy strikes and the relatively smaller number of Russian missile strikes may have eased pressure on Ukrainian air defenses in rear areas and allowed Ukrainian forces to strengthen air defense coverage along the front. Ukrainian Air Force Spokesperson Colonel Yuriy Ihnat stated on December 24 that Ukrainian forces can deploy air defense systems in any direction and not only in those where Russian forces have recently suffered aviation losses.[43] The Russian military’s increased use of missiles in the December 29 strike likely intends in part to reapply pressure on Ukraine’s limited air defense umbrella and prevent the Ukrainian command from redeploying air defense systems from the rear towards the front.

Western aid remains vital for Ukraine’s ability to defend against Russian strikes, and the end of such aid would likely set conditions for an expanded Russian air campaign In Ukraine. Ukrainian air defenses, in part buttressed by Western-provided systems and missiles, are crucial for Ukraine’s ability to intercept Russian missiles and drones throughout Ukraine, especially as Ukrainian officials have indicated that Ukraine lacks enough air defenses to evenly cover the country. Ukrainian air defenses have proven successful at pushing Russian aircraft and glide bombs away from Ukrainian cities and even the frontline in some areas. Western–provided air defense systems have thus kept Ukraine’s cities safe from bombing raids, which the Russian military would almost certainly begin to devastating effect in the absence of such systems.[44] Russia’s inability to establish air superiority has helped Ukrainian forces prevent large-scale Russian advances along the entire line of contact. United Kingdom (UK) Defense Secretary Grant Shapps stated on December 29 that the UK would send about 200 air defense missiles to Ukraine following Russia’s large-scale strike.[45] Western aid packages have in part focused on air defense systems and missiles recently, and the continuation of such aid is vital for continued Ukrainian defense of its people and its territory. ISW continues to assess that the collapse of Western aid would likely lead sooner or later to the advance of Russian forces far to the west and likely all the way to western Ukraine along the border with NATO member states.[46]

Western leaders largely viewed the massive Russian strike as evidence that Putin’s maximalist goals in Ukraine remain unchanged, in line with ISW’s long-standing assessment that Putin is not genuinely interested in a ceasefire or any sort of negotiated settlement in Ukraine. US President Joe Biden stated that the large-scale Russian strikes on Ukraine are a reminder that Putin’s objective – to “obliterate Ukraine” and “subjugate its people” – remains unchanged.[47] Biden also stated that the stakes of the war in Ukraine affect the entirety of NATO and European security, as ISW has previously suggested.[48] United Kingdom (UK) Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas stated that the Russian strikes demonstrate that Putin intends to achieve his maximalist war aims of “eradicating freedom and democracy” and destroying Ukraine.[49] ISW has consistently assessed that, despite reports of Putin’s backchannel signals about his interest in ceasefire negotiations, Russia’s goals in Ukraine – which are tantamount to full Ukrainian and Western surrender and which have been clearly stated in Kremlin public rhetoric – remain the same.[50]

Key Takeaways:

- Russian forces conducted the largest series of missile and drone strikes against Ukraine since the start of the full-scale invasion on the morning of December 29.

- The strike package that Russian forces launched on December 29 appears to be a culmination of several months of Russian experimentation with various drone and missile combinations and efforts to test Ukrainian air defenses.

- Russia will continue to conduct strikes against Ukraine at scale in an effort to degrade Ukrainian morale and Ukraine’s ability to sustain its war effort against Russia.

- Current Russian missile and drone reserves and production rates likely do not allow Russian forces to conduct regular large-scale missile strikes, but likely do allow for more consistent drone strikes, which can explain the recent pattern of Russian strike packages.

- The Kremlin’s efforts to sufficiently mobilize Russia’s defense industrial base (DIB) in support of its wartime objectives, including large-scale strike series, may been more successful than Western officials previously assessed due in part to Russia’s ability to procure military equipment from its partners and the redistribution of Russia’s resources for military production purposes.

- Russian forces have likely routinely attempted to draw and fix limited Ukrainian air defense systems away from the front, and the Russian strikes on December 29 follow recent indications that Ukrainian air defenses may be presenting significant challenges to Russian aviation operations along the frontline.

- Western aid remains vital for Ukraine’s ability to defend against Russian strikes, and the end of such aid would likely set conditions for an expanded Russian air campaign In Ukraine.

- Western leaders largely viewed the massive Russian strike as evidence that Putin’s maximalist goals in Ukraine remain unchanged, in line with ISW’s long-standing assessment that Putin is not genuinely interested in a ceasefire or any sort of negotiated settlement in Ukraine.

- Russian forces made recent confirmed advances northeast of Bakhmut and south of Avdiivka as positional engagements continued across the entire line of contact.

- The Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD) announced on December 29 that it has completed Russia’s autumn 2023 conscription cycle, which began on October 1.

- Russia continues the forced integration of occupied areas of Ukraine into the Russian system using social services and infrastructure restoration projects.

We do not report in detail on Russian war crimes because these activities are well-covered in Western media and do not directly affect the military operations we are assessing and forecasting. We will continue to evaluate and report on the effects of these criminal activities on the Ukrainian military and the Ukrainian population and specifically on combat in Ukrainian urban areas. We utterly condemn Russian violations of the laws of armed conflict and the Geneva Conventions and crimes against humanity even though we do not describe them in these reports.

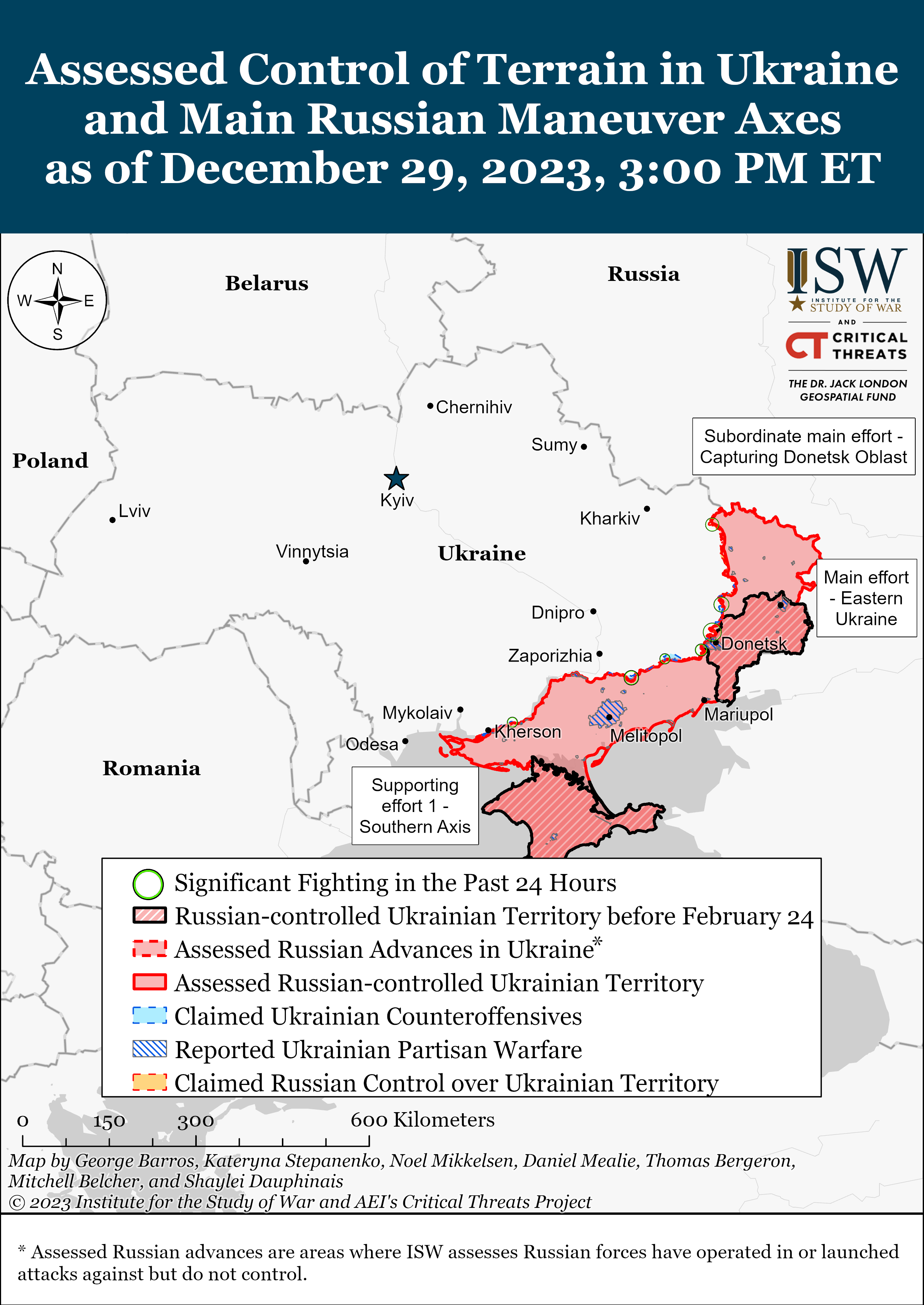

- Russian Main Effort – Eastern Ukraine (comprised of two subordinate main efforts)

- Russian Subordinate Main Effort #1 – Capture the remainder of Luhansk Oblast and push westward into eastern Kharkiv Oblast and encircle northern Donetsk Oblast

- Russian Subordinate Main Effort #2 – Capture the entirety of Donetsk Oblast

- Russian Supporting Effort – Southern Axis

- Russian Mobilization and Force Generation Efforts

- Russian Technological Adaptations

- Activities in Russian-occupied areas

- Russian Information Operations and Narratives

Russian Main Effort – Eastern Ukraine

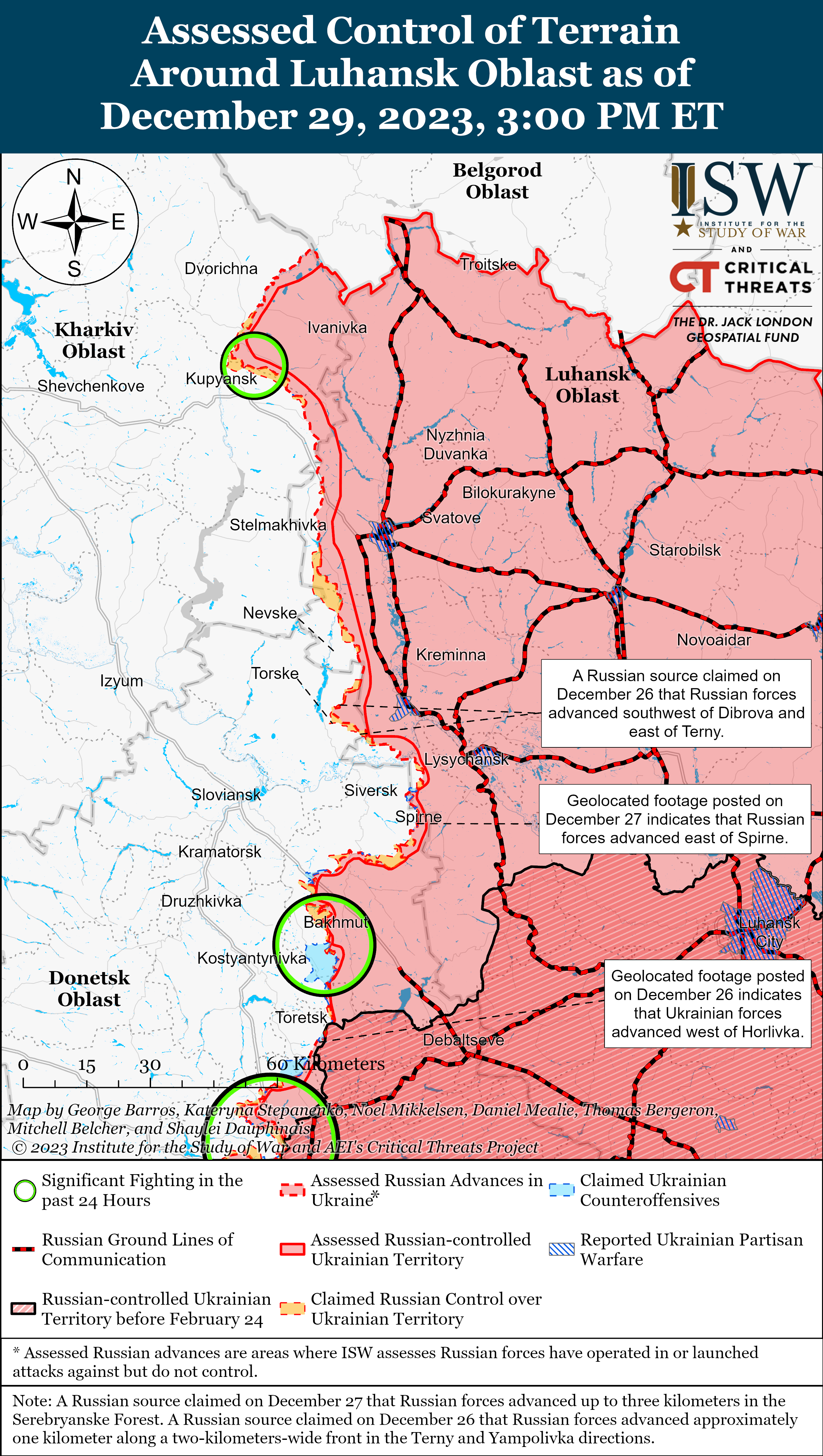

Russian Subordinate Main Effort #1 – Luhansk Oblast (Russian objective: Capture the remainder of Luhansk Oblast and push westward into eastern Kharkiv Oblast and northern Donetsk Oblast)

Russian and Ukrainian forces continued positional engagements along the Kupyansk-Kreminna line, but there were no confirmed changes to the frontline on December 29. Ukrainian and Russian sources stated that positional engagements continued northeast of Kupyansk near Synkivka and west and southwest of Kreminna near Torske and the Serebryanske forest area.[51] Ukrainian journalist Yuriy Butusov posted footage showing Ukrainian drone operators and artillery units striking a Russian armored column reportedly near Synkivka.[52]

Russian Subordinate Main Effort #2 – Donetsk Oblast (Russian objective: Capture the entirety of Donetsk Oblast, the claimed territory of Russia’s proxies in Donbas)

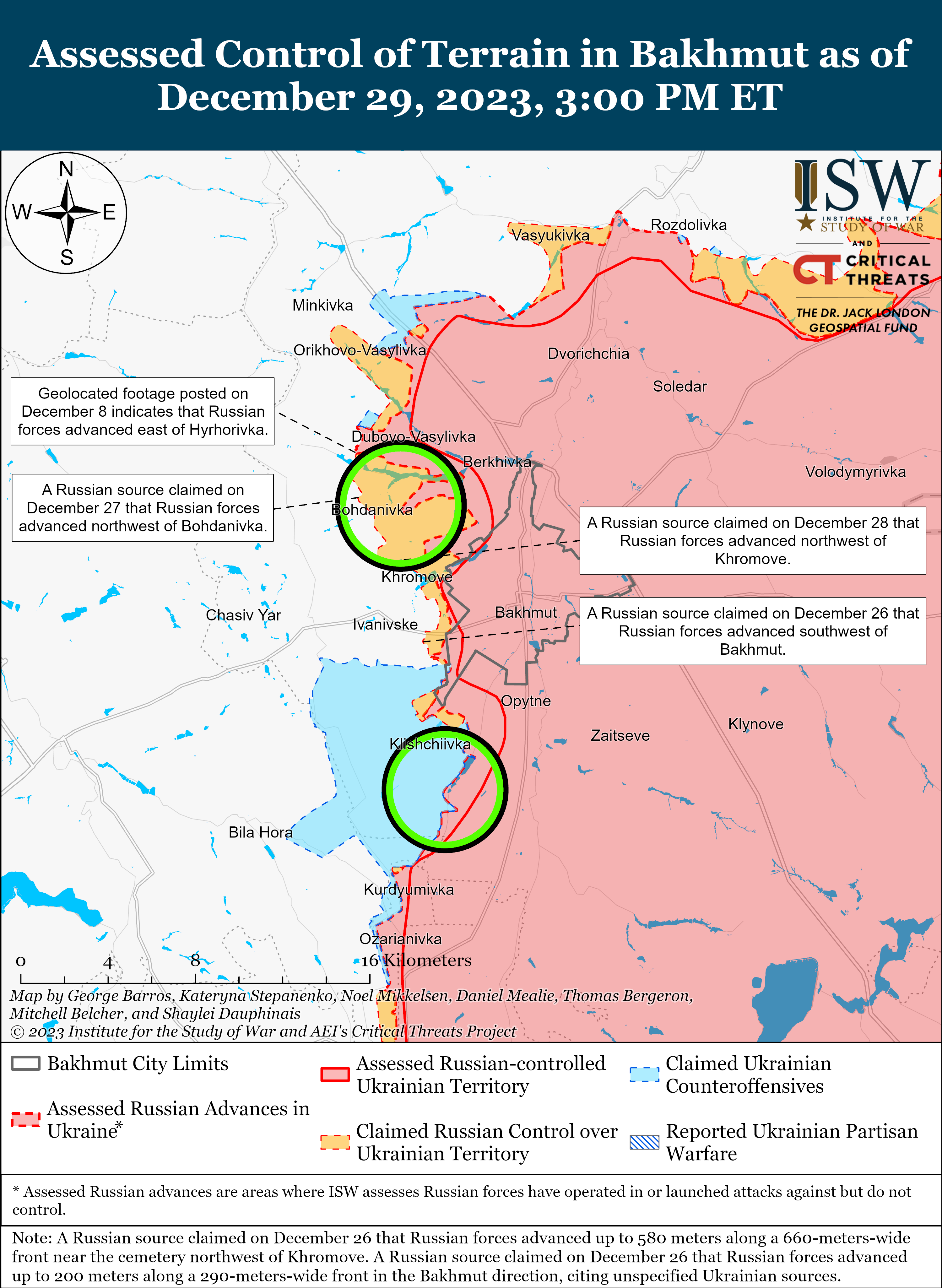

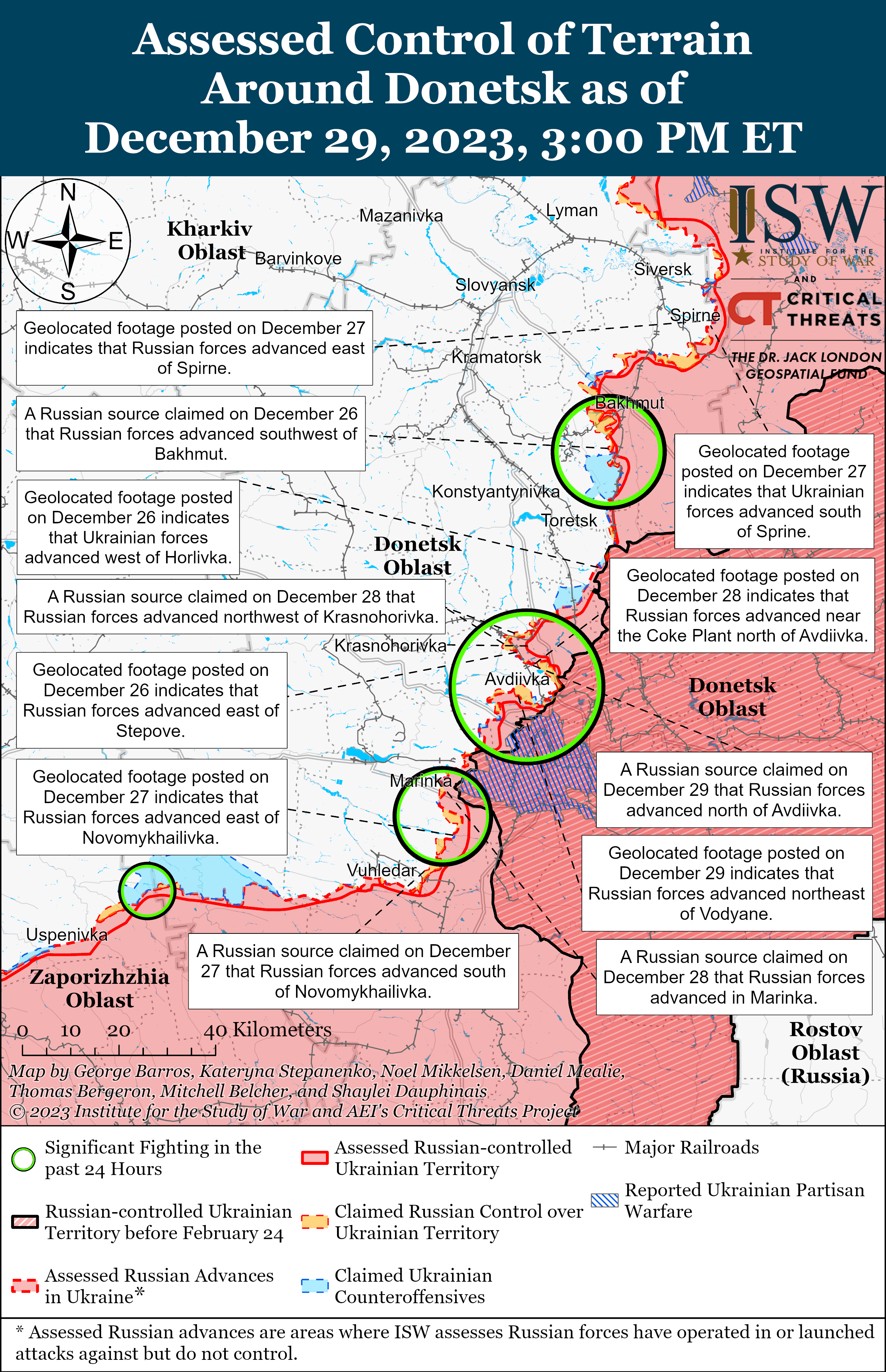

Ukrainian forces recently advanced northeast of Bakhmut as positional fighting continued in the area on December 29. Geolocated footage published on December 27 indicates that Ukrainian forces advanced south of Spirne (27km northeast of Bakhmut).[53] A Kremlin-affiliated milblogger claimed on December 28 that Russian forces marginally advanced south of Spirne.[54] The milblogger also claimed that “the fog of war” is obscuring the situation northeast of Bakhmut near Siversk but that there are no signs of major Ukrainian or Russian offensive operations in the direction of Siversk.[55] Russian sources published footage on December 29 claiming to show elements of the Russian 6th Motorized Rifle Brigade (2nd Luhansk People’s Republic [LNR] Army Corps [AC]) operating near Spirne.[56]

Geolocated footage confirms that Russian forces previously advanced near Bakhmut, while Russian and Ukrainian forces continued positional engagements in the area on December 29. Recently geolocated footage originally published on December 8 indicates that Russian forces previously advanced east of Hryhorivka (9km northwest of Bakhmut).[57] Russian milbloggers claimed on December 29 that Russian forces advanced near Bohdanivka and Andriivka.[58] Ukrainian and Russian sources stated that positional fighting continued west of Bakhmut near Bohdanivka, Khromove, and Ivanivske and southwest of Bakhmut near Klishchiivka, Andriivka, and Kurdyumivka.[59] Russian sources published footage claiming to show elements of the “Shustry” Detachment of Chechen “Akhmat” Spetsnaz, the Russian 4th Motorized Rifle Brigade (2nd LNR AC), and the 137th Guards Airborne (VDV) Regiment (106th Guards VDV Division) operating near Bakhmut.[60]

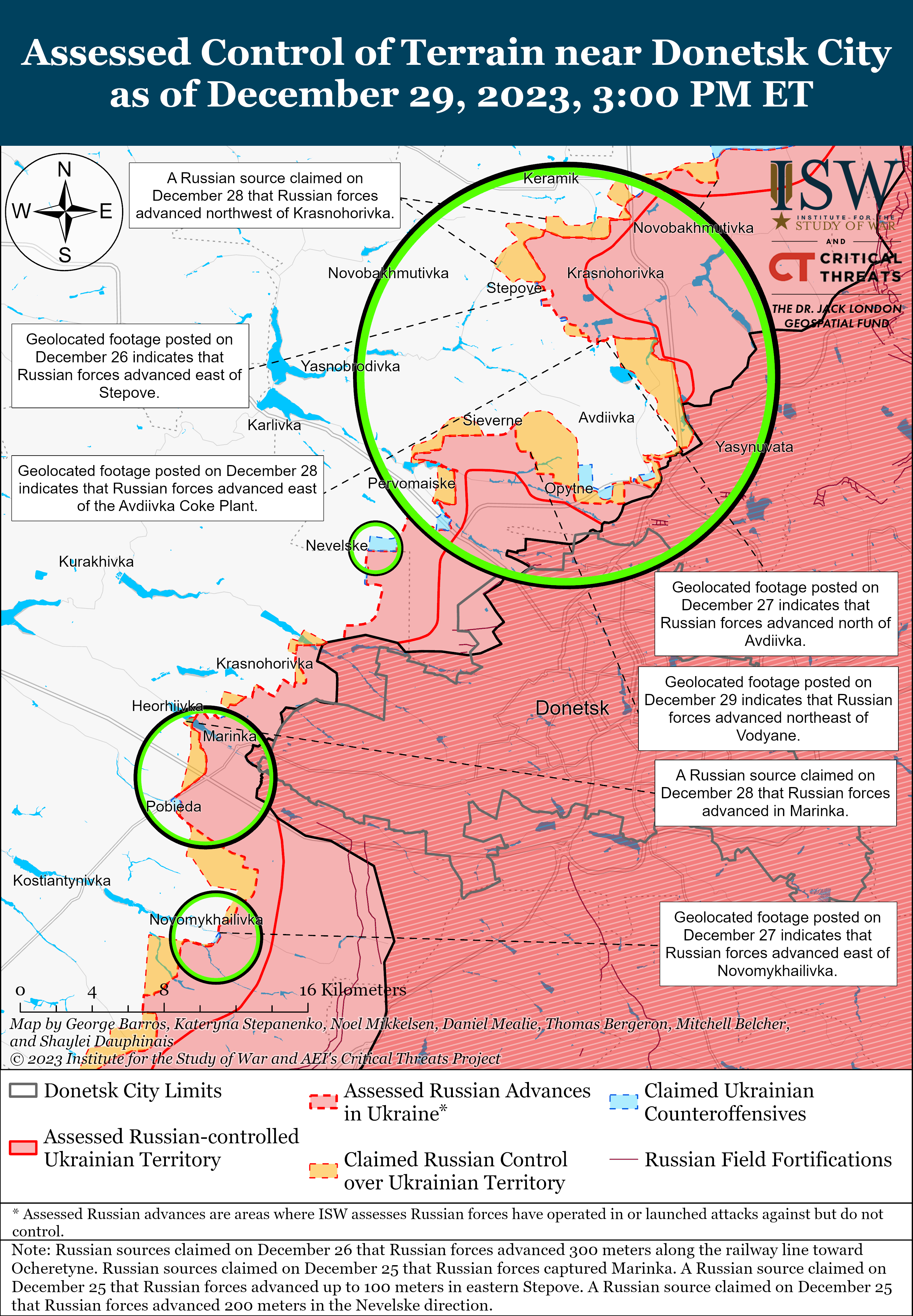

Russian forces recently advanced south of Avdiivka as positional engagements continued around the settlement on December 29. Geolocated footage published on December 29 indicates that Russian forces advanced northeast of Vodyane (7km southwest of Avdiivka).[61] Russian sources claimed that Russian forces also advanced northwest of Avdiivka near Krasnohorivka and towards the Avdiivka Coke Plant, although ISW has not observed visual evidence of such advances.[62] Ukrainian and Russian sources claimed that positional fighting continued northwest of Avdiivka near Ocheretyne, Novobakhmutivka, and Stepove; southeast of Avdiivka near the industrial zone; and southwest of Avdiivka near Sieverne, Pervomaiske, and Nevelske.[63] Ukrainian military observer Kostyantyn Mashovets stated that Russian forces are attacking in small assault groups without armored vehicle support, and in some cases without artillery support, relying instead on small arms fire.[64] Mashovets added that elements of the Russian 15th Separate Guards Motorized Rifle Brigade (2nd Guards Combined Arms Army [CAA], Central Military District [CMD]), 21st Separate Guards Motorized Rifle Brigade (2nd CAA, CMD), 74th Separate Guards Motorized Rifle Brigade (41st CAA, CMD), and 35th Separate Guards Motorized Rifle Brigade (41st CAA, CMD) are attempting to advance northwest and southwest of Avdiivka.[65]

Russian and Ukrainian forces continued positional fighting west and southwest of Donetsk City on December 29, but there were no confirmed changes to the frontline in this area. Russian and Ukrainian sources stated that positional fighting continued near Marinka (west of Donetsk City) and Novomykhailivka (southwest of Donetsk City).[66] A Russian milblogger published footage on December 28 claiming to show elements of the Russian 11th Army Corps striking Ukrainian forces with an Izdeliye loitering munition near Novomyhailivka.[67] Another milblogger claimed that elements of the Russian 255th Motorized Rifle Regiment (20th Motorized Rifle Division, 8th CAA, Southern Military District [SMD]) are operating near Marinka.[68] The Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD) recognized elements of the Russian 150th Motorized Rifle Division (8th CAA, SMD) and the 5th Separate Motorized Rifle Brigade (1st Donetsk People’s Republic [DNR] Army Corps) for their reported role in the Russian capture of Marinka.[69]

Russian Supporting Effort – Southern Axis (Russian objective: Maintain frontline positions and secure rear areas against Ukrainian strikes)

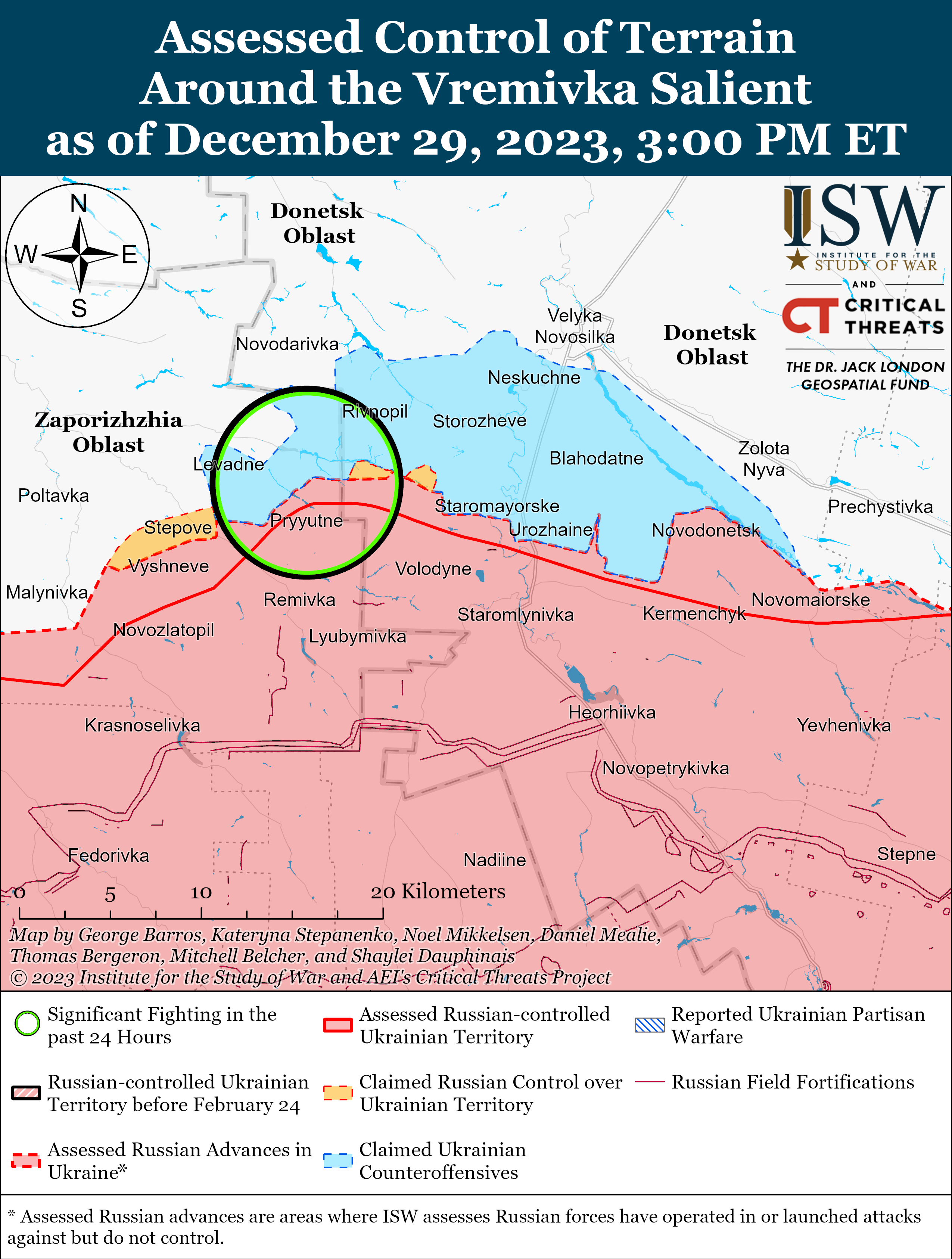

Russian and Ukrainian forces continued positional engagements in the Donetsk-Zaporizhia Oblast border area on December 29, but there were no confirmed changes to the frontline in this area. A Russian milblogger claimed that Russian forces attacked from Pryyutne towards Novodarivka (both southwest of Velyka Novosilka) in an effort to expose Ukrainian positions in Staromayorske (south of Velyka Novosilka) to attacks from the west along the Pryyutne-Novodarivka line.[70] The Ukrainian General Staff reported that Ukrainian forces repelled four Russian attacks south of Novodarivka.[71] Elements of the Russian 36th Combined Arms Army (CAA) (Eastern Military District [EMD]) and 36th Motorized Rifle Brigade (29th CAA, EMD) reportedly continue operating in this area.[72]

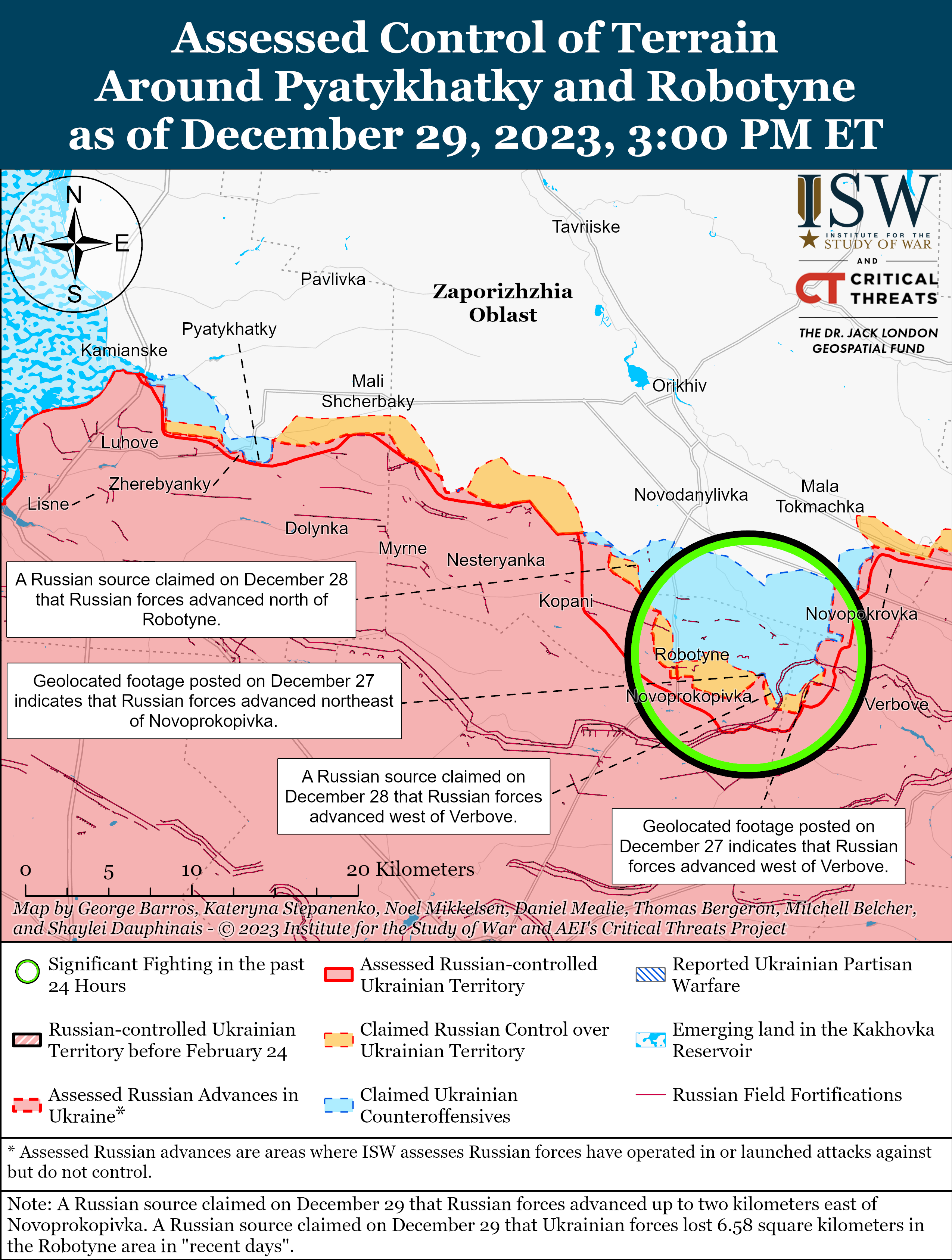

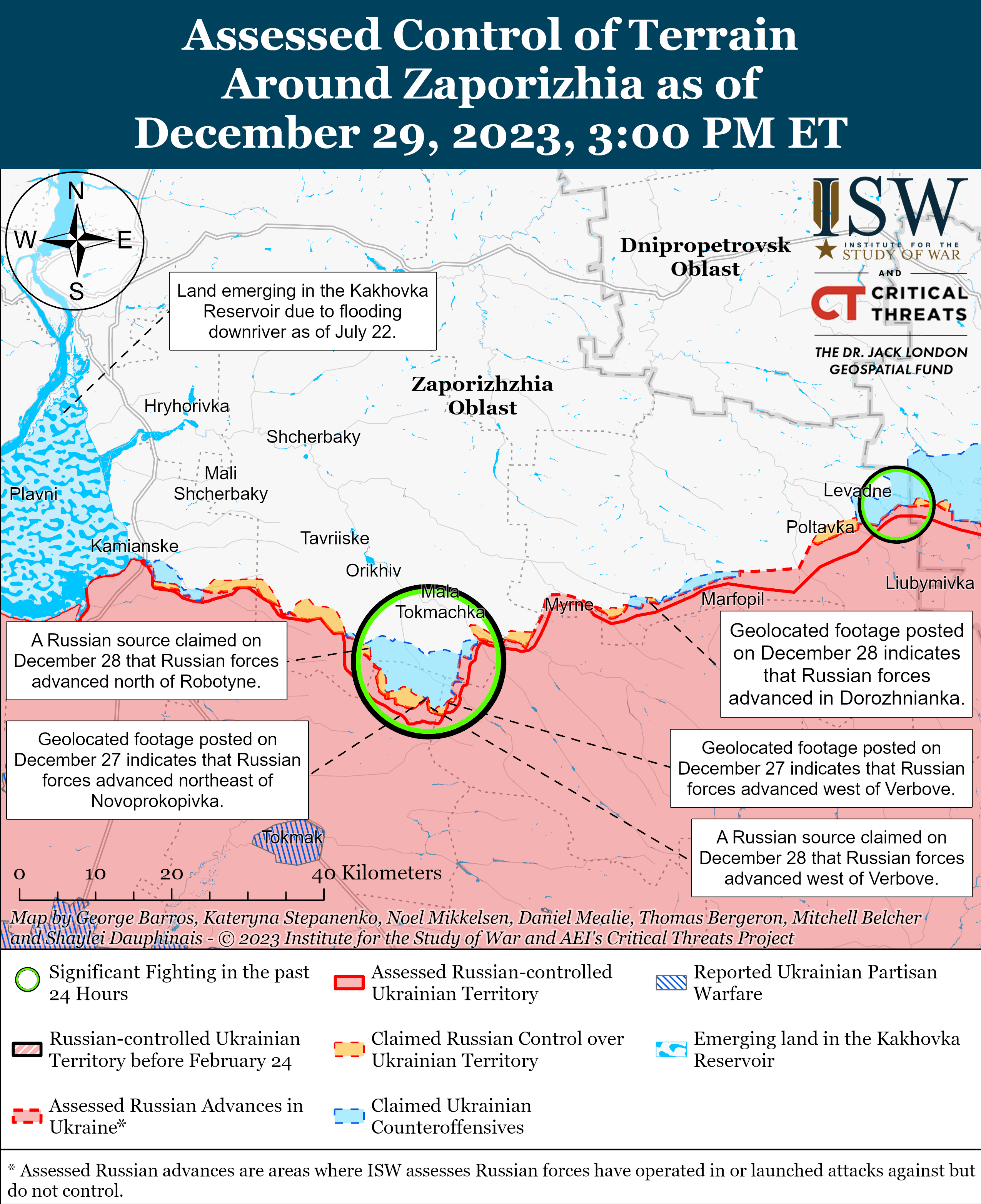

Russian forces continued efforts to regain previously lost positions in western Zaporizhia Oblast on December 29, but there were no confirmed changes to the frontline in this area. A Russian milblogger claimed that Russian forces advanced up to two kilometers deep east of Novoprokopivka (south of Robotyne), although ISW has not seen visual evidence of this advance.[73] Ukrainian military observer Kostyantyn Mashovets noted that elements of the 7th and 76th Airborne (VDV) Divisions have managed to restore lost positions in this area in the last two to three days and have pushed Ukrainian forces out of some positions north and west of Verbove (east of Robotyne).[74] Russian and Ukrainian sources reported that positional engagements continued along the Kopani-Robotyne-Novoprokopivka-Verbove line, particularly around Robotyne and between Novoprokopivka and Verbove.[75] Elements of the Russian 7th and 76th VDV Divisions, 136th Motorized Rifle Brigade (58th CAA, Southern Military District [SMD]), and 71st Motorized Rifle Regiment (42nd Motorized Rifle Division, 58th CAA, SMD) reportedly continue operating in this area.[76]

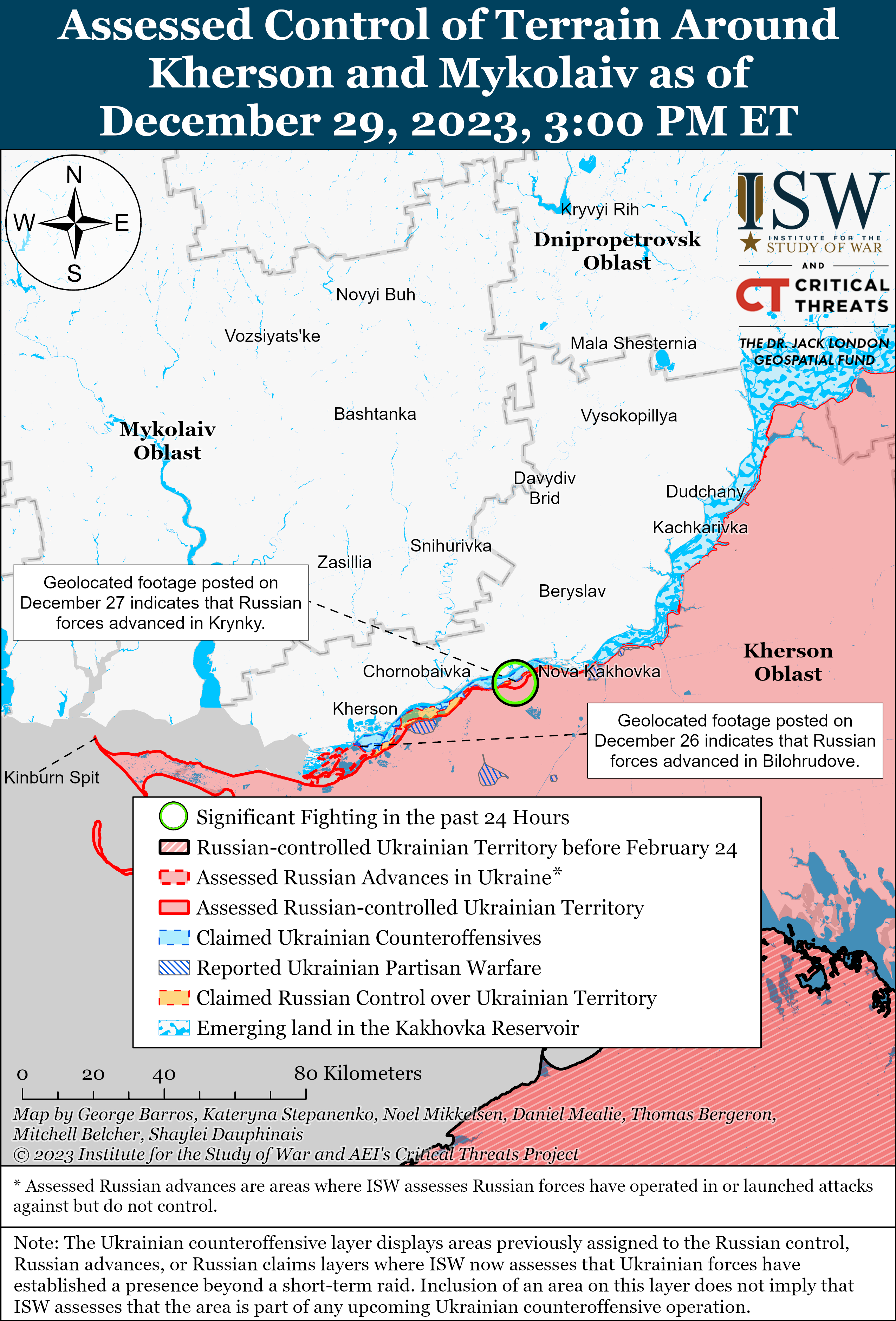

Ukrainian forces maintain positions on the east (left) bank of Kherson Oblast as of December 29, but there were no confirmed changes to the frontline in this area. Russian and Ukrainian sources reported positional engagements near and in Krynky.[77] Elements of the Russian VDV and unspecified Spetsnaz elements reportedly continue to operate in the area.[78]

Russian Mobilization and Force Generation Efforts (Russian objective: Expand combat power without conducting general mobilization)

The Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD) announced on December 29 that it has completed Russia’s autumn 2023 conscription cycle, which began on October 1.[79] The Russian MoD stated that it inducted 130,000 people for conscript service according to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s September 29, 2023, conscription decree.[80] The Russian MoD added that most conscripts enrolled in training formations and military units and that the Russian military discharged conscripts from the autumn 2022 conscription cycle who served the established terms of their conscript service.[81] The Russian MoD previously stated at the beginning of the autumn 2023 conscription cycle that conscripts would not deploy to occupied Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhia, or Kherson oblasts or participate in combat operations in Ukraine.[82] ISW has not observed conscripts fighting in Ukraine since the first months of Russia’s full-scale invasion but has observed Russian security forces increasingly relying on conscripts for border security functions along Russia’s international border with Ukraine.[83] The Russian State Duma will reportedly consider a proposed bill allowing Russian conscripts to serve in the Federal Security Service’s (FSB) Border Service.[84] ISW continues to assess that the Kremlin remains unlikely to deploy conscripts to participate in combat operations in Ukraine due to concerns that it may cause discontent within Russia.[85] Russia will conduct its spring 2024 conscription cycle from April 1 to July 15, 2024.[86]

Kremlin newswire TASS reported on December 29 that information from the Russian MoD indicates that Russian forces received 1,500 tanks, 2,200 armored fighting vehicles, 1,400 armored vehicles, 1,400 rocket-artillery systems, and 22,000 drones in 2023.[87] TASS did not indicate what portion of this equipment Russian forces pulled from storage and what percentage was newly produced.[88] Russia has gradually been mobilizing its defense industrial base (DIB) to support the war effort in Ukraine but has not done so at a scale that would suggest that most of the reported transfers of military vehicles to Russian forces in 2023 represent newly produced vehicles.[89]

Russian Technological Adaptations (Russian objective: Introduce technological innovations to optimize systems for use in Ukraine)

Kalashnikov Concern subsidiary and manufacturer of the Russian “Lancet” loitering munition Zala Aero stated on December 29 that it is developing the short-range “Izdeliye 55” loitering munition.[90] Zala Aero claimed that Russian specialists are designing the “Izdeliye 55” loitering munition to be resistant to the effects of Ukrainian electronic warfare complexes.[91]

Activities in Russian-occupied areas (Russian objective: Consolidate administrative control of annexed areas; forcibly integrate Ukrainian citizens into Russian sociocultural, economic, military, and governance systems)

Russia continues the forced integration of occupied areas of Ukraine into the Russian system using social services and infrastructure restoration projects. The Russian government approved a resolution on December 29 that defines the main goals of the state program for the “Rehabilitation and socio-economic development” of occupied Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhia, and Kherson oblasts.[92] The resolution emphasizes the restoration of housing, utilities and transportation infrastructure; social developments; and encouragement of private investment to bring the occupied areas up the “average Russian indicators of quality of life” by 2030, and relies on federal subsidies to do so. Russian occupation authorities continue to use the threshold of Russian living standards to generate dependencies on Russian social service provisions and infrastructure projects amongst residents of occupied Ukraine, thereby solidifying the integration of these areas into the Russian system.

Russia is using the provision of medical care as a coercive device in occupied Ukraine. Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin stated on December 29 that it is vital for Russian officials to provide residents of occupied Ukraine with quality medical services and the “best Russian medical practices.”[93] Mishustin emphasized that blood banks should operate up to Russian standards in occupied Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhia, and Kherson oblasts.[94] Ukrainian Melitopol Mayor Ivan Fedorov, however, noted on December 29 that starting January 1, 2024, Russian occupation authorities will begin providing medical care only to those eligible for Russian healthcare, which requires the recipient to have a Russian passport.[95] ISW has observed previous instances of Russian authorities using the promise of medical care to incentivize passportization in occupied Ukraine.[96] Russian occupation authorities have previously withheld access to critical drugs, such as insulin, to those without Russian passports.[97]

Russian Information Operations and Narratives

The Ukrainian Main Military Intelligence Directorate (GUR) stated on December 29 that the Kremlin may consider conducting information operations aimed at weaponizing expected opposition to mobilization in Ukraine to sow regional divisions and instability.[98] The GUR stated that analysts close to the Kremlin proposed several subversive hybrid warfare campaigns aimed at discrediting the Ukrainian mobilization process in order to cause large-scale population outflow from Ukraine and regional divisions between Ukrainian oblasts, potentially by pitting southeastern regions of Ukraine against Kyiv Oblast and western Ukraine

Prominent Russian milbloggers, including one whom the Kremlin and Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD) have previously awarded for service to the Russian Armed Forces, continued to reiterate Kremlin narratives and thinly veiled threats aimed at Finland’s security as a NATO member on December 29.[99]

Significant activity in Belarus (Russian efforts to increase its military presence in Belarus and further integrate Belarus into Russian-favorable frameworks and Wagner Group activity in Belarus)

Nothing significant to report.

Note: ISW does not receive any classified material from any source, uses only publicly available information, and draws extensively on Russian, Ukrainian, and Western reporting and social media as well as commercially available satellite imagery and other geospatial data as the basis for these reports. References to all sources used are provided in the endnotes of each update.

[7] https://armyinform.com dot ua/2023/12/29/volodymyr-zelenskyj-rosiya-vypustyla-pryblyzno-110-raket-bilshu-chastynu-zbyto/; https://suspilne dot media/649808-ataka-droniv-na-odesu-ta-mozliva-zustric-zelenskogo-i-orbana-674-den-vijni-onlajn/?anchor=live_1703838193&utm_source=copylink&utm_medium=ps

[30] https://www.sueddeutsche dot de/projekte/artikel/politik/ukraine-russland-krieg-bundeswehr-verteidigung-e611912/?reduced=true ; https://suspilne dot media/650432-general-bundesveru-nimeccina-nedoocinila-mozlivosti-rosii-z-virobnictva-zbroi-dla-vijni-proti-ukraini/

[31] https://www.sueddeutsche dot de/projekte/artikel/politik/ukraine-russland-krieg-bundeswehr-verteidigung-e611912/?reduced=true ; https://suspilne dot media/650432-general-bundesveru-nimeccina-nedoocinila-mozlivosti-rosii-z-virobnictva-zbroi-dla-vijni-proti-ukraini/

[34] https://meduza dot io/feature/2023/12/29/ves-god-rossiyskaya-ekonomika-rosla-blagodarya-voyne-tak-budet-i-v-2024-m

[35] https://meduza dot io/feature/2023/12/29/ves-god-rossiyskaya-ekonomika-rosla-blagodarya-voyne-tak-budet-i-v-2024-m ; https://publications dot bof.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/53201/bpb1623.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[36] https://meduza dot io/feature/2023/12/29/ves-god-rossiyskaya-ekonomika-rosla-blagodarya-voyne-tak-budet-i-v-2024-m

[37] https://meduza dot io/feature/2023/12/29/ves-god-rossiyskaya-ekonomika-rosla-blagodarya-voyne-tak-budet-i-v-2024-m

[38] https://meduza dot io/feature/2023/12/29/ves-god-rossiyskaya-ekonomika-rosla-blagodarya-voyne-tak-budet-i-v-2024-m

[98] https://gur dot gov.ua/content/rehionalni-rozkoly-rosiia-vvazhaie-za-neobkhidne-zruinuvaty-iednist-vseredyni-ukrainy.html