Kampala, Uganda – This January, when Bobi Wine learned that the film documenting his 2021 Ugandan presidential bid had been nominated for an Academy Award, he was hiding from the police.

The swaggering popstar-turned-opposition leader had been on the run for five days, not sleeping or showering. This was after security forces cordoned off his home in response to his calls for protests over the poor road conditions in Uganda as the Non-Aligned Movement’s summit held in the capital Kampala.

Wine, whose real name is Robert Kyagulanyi, was shocked by the nomination. “I screamed,” he said. “If there was any police officer nearby, I would have been arrested immediately.”

The nomination of Bobi Wine: The People’s President for Best Documentary Feature at the Oscars marks the first time a Ugandan film has earned recognition from the Academy Awards.

But while it has led to celebration within Wine’s camp, the film is also a surreal reminder of the many challenges the 41-year-old politician has had to confront in his relatively short political career.

Filmed over five years, it begins with singer Wine’s election to the Ugandan parliament in 2017 and shows his meteoric rise through politics, becoming the face of a vibrant youth movement.

In impassioned speeches, the newly minted politician decries a constitutional amendment abolishing presidential age limits. But despite his opposition, the bill passed and allowed incumbent Yoweri Museveni, who seized power in 1986, to run for another term.

Another scene follows Wine through the Kamwookya slum where he grew up, as he sings of freedom and calls on people to rise.

A year later, the documentarians are with as Wine as he recovers from torture and a failed assassination attempt, briefly travelling to the United States for treatment.

“Museveni used to be my favourite revolutionary,” he tells filmmakers in a car rolling through downtown Washington, DC. “I would really love to have a frank and honest conversation with him.”

A disputed election

A desire for change propelled Wine to challenge Museveni for the presidency in what he hoped would be Uganda’s first democratic election, excitedly announcing his candidacy shortly after returning home in July 2019.

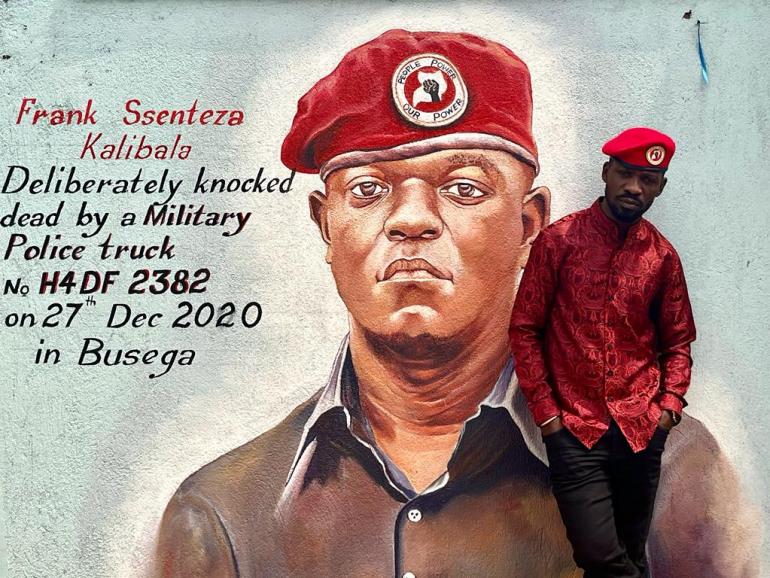

But the result was a bloody and contested vote as the ruling party clamped down on the opposition. Even before the election, at least 54 people were shot after riots broke out following Wine’s temporary detention in the city of Jinja in November 2020. Other supporters were jailed or attacked on the campaign trail.

In the film, the camera zooms in as Wine dodges bullets and teargas, wavering only when the documentarians have to duck for cover themselves.

“I was arrested a few times. I was interrogated,” said Moses Bwayo, a Ugandan journalist and one of the film’s directors. In the final days of the campaign, he was shot in the face with a rubber bullet.

Still, Bwayo kept recording. “All these threats and everything that was happening really emboldened me to tell this story, and carry the task forward,” he said. As election day approached, he moved into Wine’s home.

Afterwards, Bwayo filmed Wine and his wife Barbie Kyagulanyi listening to a radio broadcast announcing Museveni as victor. Their faces are numb with shock and disbelief.

Wine called for more protests over the election results, but large-scale demonstrations never materialised following a brutal campaign and disappointing result.

Deciding he was no longer safe in Uganda, Bwayo captured a final scene of Bobi Wine once again singing songs of freedom in Kamwookya.

Then, Bwayo escaped Uganda with his wife.

“We fled like we were going on a small trip,” he said. “We landed in the United States, and we applied for political asylum.”

They are still awaiting a decision.

Documenting repression

This week, Wine told Al Jazeera that the film is a documentation of all he suffered and the challenges still facing his homeland.

“We’ve been able to present the reality in Uganda, uncensored and unedited, to the international community,” the opposition leader said.

“It showcases the brutality of the Museveni regime, but also the resilience of the Ugandan people in pushing back against impunity, against injustice,” added David Lewis Rubongoya, secretary-general of Wine’s National Unity Platform political party.

The threat of harsh repression still hangs over the Ugandan population, analysts assert. But Museveni, who has now been in power for some 38 years, is becoming increasingly paranoid as another election looms on the horizon.

“[Violence] may have succeeded in the short run, in terms of preventing … a wide protest movement from emerging after the polls,” Michael Mutyaba, a Ugandan academic at SOAS University of London, said of the 2021 vote. “But if you look at it in the long term, I don’t think it succeeded.”

“What it did was expose the regime more to international criticism and reveal things that it had maybe successfully concealed for a long time,” Mutyaba told Al Jazeera.

‘Our story’

Meanwhile, Bwayo and Christopher Sharp, the film’s other director, trimmed 4,000 hours of footage to just a few hours of runtime

The documentary debuted at the 79th Venice Film Festival in 2022. It was then acquired by National Geographic, which supported a theatrical release last year. The Oscar nomination followed this year.

The filmmakers hope their work will bring renewed attention to Uganda and its citizens.

“We’re fooling ourselves in the West, and we’re being very disrespectful to the people of Uganda, to pretend that they’re living in a democracy, that those elections are anything other than a sham,” said Sharp, who is also one of the documentary’s producers.

For Wine, the film is a lifeline.

“The more our story is out there, the more we are able to live and see the sun the following day,” he told Al Jazeera.

On Friday, which also marks the anniversary of Museveni taking power, Wine and his followers attempted to mount a public screening of the film. Security personnel deployed heavily along the road, intimidating people travelling to see the film.

Attending with two of his children, Wine sang again, telling supporters everything would someday be alright.